Grand Traverse County needs a new jail.

Community advocates say it. People who have been incarcerated say it. Even the sheriff, who runs the jail, says it.

It’s not a new idea; the conversation has been going on for at least two decades. But there has been very little progress on actually making any improvements happen.

Ramon Fernandez knows the condition of the Grand Traverse County Jail well. He’s been incarcerated a number of times over the years.

“That jail hasn't changed,” he said. “It's just getting older and older and older and almost seems like it's getting darker and darker and darker.”

He says on a typical day he would draw but other than that, there's not much to do. There are a few programs to get inmates out of their cells and occupied, but the jail is limited by its physical space, only having room for one program at a time.

“We're lucky to go to a gym maybe once a week,” Fernandez said. “Really, there's nothing there. You just walk around in circles. There’s just no room.”

So if there was one thing to change?

“Space. Space,” he said. “Heck, I think about animals on a farm that have more space to live and be able to just breathe.”

One of the programs Fernandez did get involved in was the weekly Catholic worship services. It was there that he met Tom Bousamra, the president of the non-profit Before, During, and After Incarceration, and was able to get connected to more resources.

“I was a very proud man before,” Fernandez said. “I didn't want to ask for help. …You can get caught in this vicious cycle.”

Bousamra is a Catholic deacon and has been involved in jail ministry for 38 years, all at the same 1964 building.

And while he and his non-profit primarily work directly with incarcerated individuals, they’ve also increased their push for more systemic change on the county level — including better conditions at the Grand Traverse County Jail.

The latest push came after the county recently assessed its buildings, including the jail.

“They’re dissatisfied with all their public facilities,” Bousamra said, “so they did an assessment, including in that a new jail. ... I picked up the ball and wanted them to look at it as phase one. Move that up. We need a jail now, not three or four years from now.”

He says the personnel running that jail have improved throughout the years. They’ve hired a new social worker — a big plus, he says — and are planning to hire a discharge planner who will help people transition back into the world upon their release.

Bousamra’s problem isn’t with the staff. It’s the building itself.

“I give the sheriff quite a bit of credit for trying to move the needle on human dignity and a humane approach, but we still have the dark facility,” he said.

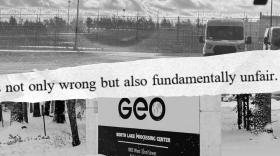

It’s not just Grand Traverse County that is having this issue. Jails and prisons all over the country are aging.

One third of all federal prisons are over 50 years old. The Federal Bureau of Prisons reported a repair backlog of about $3 billion last year. Only $179 million of that was allocated to the agency by Congress in a fiscal package — about 6% of what’s needed to address the backlog.

Inside the jail

Grand Traverse County Sheriff Michael Shea acknowledges the jail’s outdated design. The building, he says, was put up when people had different ideas about incarceration.

“This current facility, which was originally built in the early 1960s, was designed to hold inmates in, and it functions very well that way,” said Shea, who was appointed to the job after Sheriff Tom Bensley’s retirement in 2023, and won election to the office last November. “What has changed drastically is our inmate population.”

When Bensley retired in 2023, he told the Traverse City Record-Eagle that the jail was “the biggest liability the county has.”

The broader trend in law enforcement has moved farther away from simply housing inmates and more towards rehabilitation.

“We have become the local state hospital, if you will,” Shea said. “We have 38 percent of our population at the last study suffering from serious mental health issues. Sixty-plus percent suffer from some sort of mental health as well as substance use disorder or coexisting disorders. We're not designed to deal with and accommodate that type of a population.”

There are a number of ways the jail’s design affects inmates' mental health. For one, there’s little natural light — only a few windows, really. There’s no access to a yard.

For some cells, the most natural light they will get will be their weekly visit to the gym, which has a retractable roof.

But besides the mental health aspect, Shea says the age of the jail is a concern.

“Our infrastructure is shot. We have valves that can't be shut off,” he said. “We have parts to certain locking mechanisms that are nonexistent if they break. You either have to have someone manufacture them, or you piece them back together.”

“We have parts to certain locking mechanisms that are nonexistent. If they break, you either have to have someone manufacture them, or you piece them back together.”

Michael Shea

Grand Traverse County sheriff

Shea gave IPR a tour of the jail, but would not let recording equipment inside.

He pointed out decades-old leaks in the ceilings. Certain locks to cells were so old that they could no longer be replaced. And in a control room, a young officer watched more than 60 cameras for his 12-hour shift.

The guards also check the cells in person, but with the jail’s linear layout, there’s no easy way for a guard to check multiple cells at once. Shea said it’s easy to see how someone could die by hanging.

Suicide has happened a number of times in the jail, most recently in 2022.

“If the question is, ‘Will a brand new facility or a modernized facility mitigate suicides?’ the answer is no,” Shea said. “Will it help reduce? Yes, I truly believe that there are certain conditions that can be improved upon and in a new, modern facility with better observation, I think it can be reduced.”

Being the largest law enforcement agency north of Grand Rapids, Shea sees the Grand Traverse County Jail as the hub at the center of a wheel.

The spokes are smaller nearby jails — some newer like Leelanau and Wexford county — while others still need their own renovations. They all work together to keep things moving, but the Grand Traverse County Jail is at the center of it all.

And the center, Shea says, is falling apart.

The future

If the case is that apparent, why hasn’t Grand Traverse County adopted a fix?

Shea says his office and the county’s Board of Commissioners are at a stalemate.

At a board study session in October, Shea discussed the future of the jail. Commissioner Daryl Nelson said he’s aware of the problem, but wants more details about what needs to be done.

“One of the things I always see with the jail — and I don't mean the sound like I'm being critical; I'm not — but it's always the look back,” he said during the meeting. “And I guess I'd like to see the future.”

Nelson wants a financial analysis before any commitments are made. But to Shea, this seems like a promise he and his predecessors have seen before. And he said as much in the same meeting.

“I'm not going to dispute that it would be helpful,” Shea told the commissioners at that October meeting. “With no direction from the commission to what your thoughts are, it — with all due respect — is kind of a waste of our time that we just don't have. I mean, this is a 20-30 year conversation that's been ongoing.”

In a more recent conversation with IPR, Nelson expressed a need for patience and caution.

“I think the sheriff is frustrated and I think I was frustrated that the sheriff couldn’t provide a real clear answer or even kind of an idea of where they wanted to go,” he said. “I think whether it's $35 or $50 million you don't shoot from the hip.”

“I think the sheriff is frustrated and I think I was frustrated that the sheriff couldn’t provide a real clear answer or even kind of an idea of where they wanted to go."

Daryl Nelson

Grand Traverse County Board of Commissioners

So there’s a stalemate at the moment. The sheriff asks for something to be done, the board asks for detailed plans. It’s a cycle the jail conversation seems to be stuck in.

But another commissioner, TJ Andrews, thinks plans are stuck because of board inaction. She said it has to the Board of Commissioners that makes the next move.

“Because, frankly, the Board of Commissioners is the one who's going to end up having to figure out the funding mechanism for it,” Andrews said. “My suspicion is that if the board isn't behind it, it's not going anywhere. And until the board says 'This is our priority and we're going to make it happen and we're going to put the resources into it,' no one else believes it's going to happen.”

And even though there are no immediate plans for improvements, Commissioner Nelson says the jail is a priority.

“It is on the radar. I can't show you a plan. I can't show you a date,” he said. “But we're, we're very serious about looking at what we need in our county.”

In the meantime, Shea says he’ll work with what he’s got.

“We have to keep operating so we’re going to do what we need to do,” Shea said. “We just need to decide: What do we want to do? And it will, unfortunately, cost some money, we know that. But so does everything.”

And while budgets are discussed and cautions exercised, inmates keep coming into the jail, much like Ramon Fernandez, the formerly incarcerated man who is speaking out about conditions inside the jail.

“The way I see it, yes, you do have to pay and suffer the consequences, but you should also be rehabilitating. And to rehabilitate, you have to have some resources,” he told IPR. “There should be a light at the end of the tunnel that should be provided, not just be thrown into a dungeon, and say, ‘OK, you commit a crime, you're gonna do this time.’ And then that's it.”

For now, though, the building stays as is, growing — like Fernandez said — older and darker.