For thousands of years, woodland caribou were more common in the Great Lakes region than moose, elk or even deer. They’re still found in northern Canada and in Alaska, but have mostly disappeared from this region – with one exception.

On Lake Superior’s far northern shore, a small population carries on. In 2014, that last remaining herd found itself stranded on an island with hungry wolves, and by 2018 the end of the herd’s existence was in sight.

Some blame climate change for the caribou’s decline. But many experts say that’s a cop out; a reason for inaction.

For this story, Points North crosses the border and revisits a remarkable last-minute rescue. We ask what it will take to save caribou from local extinction – and if climate change can sometimes be an easy excuse for giving up.

Credits:

Producer: Patrick Shea

Editor: Morgan Springer

Host / Additional Editing: Dan Wanschura

Music: Magnus Moone, Blue Dot Sessions and Santah

Transcript:

DAN WANSCHURA, HOST: Twenty-three animal species went extinct last year in the United States alone. That’s according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It’s part of a global trend. And in many cases, climate change pushes these animals over the edge.

Today’s story is about an animal that’s a threatened species in parts of North America. But here in the Great Lakes, it’s close to local extinction. It’s an animal that made it through an ice age and through warming temperatures. It’s survived climate change before. So why is it in trouble now?

From Interlochen Public Radio, this is Points North: A show about the land, water and inhabitants of the Upper Great Lakes. I’m Dan Wanschura.

PATRICK SHEA, BYLINE: How about land, water, ice and inhabitants.

WANSCHURA: No, that’s way too long. That’s reporter Patrick Shea, by the way, jumping in early, stealing my thunder as usual.

SHEA: Sorry. But ice is a big part of this story, which is all about an animal that I didn’t even know was here.

WANSCHURA: Yeah. me neither.

SHEA: We’re talking about a certain cervid.

WANSCHURA: Wait. I know the animal’s name, but what’s a cervid?SHEA: That’s the deer family of mammals. But it’s not a deer. And it's not a moose. And it’s not an elk, either.

WANSCHURA: Alright, Patrick. Let’s just tell them.

NANCY LANGSTON: I was pretty astonished to learn that woodland caribou had once roamed all the way downstate in Michigan, throughout Minnesota, out to the great plains throughout Wisconsin…

SHEA: That’s Nancy Langston, an environmental historian who’s spent years studying caribou. She says their range has declined a lot over the last century. These days they’re mostly found in Canada’s far north, and in Alaska, too.

LANGSTON: Caribou are amazing because they were one of the so-called pleistocene megafauna: the really big, sexy animals. After the retreat of the glaciers 10,000 years ago, they were one of the very few that survived in North America. Most of the other big sexy creatures like wooly mammoths, saber-toothed tigers and the giant sloth – they went extinct. So caribou are survivors.

WANSCHURA: And the reason is, these sexy cervids are masters of evasion. Escape artists, really.

LANGSTON: Unlike moose that stand still and kick their predators in the head, and unlike whitetail deer that deal with heavy predation by just having twins every year and starting to bread really young, caribou have survived by being able to move – by being able to migrate, by being able to go through really deep snow where almost no other animal can go. They’re just really good at getting out of the way of predators.

WANSCHURA: So good that they outcompeted every other cervid in the Upper Great Lakes.

SHEA: Yeah, that’s what really blew my mind. Nancy says for thousands of years there were way more caribou in the northern Midwest than there ever were elk, moose or even deer.

WANSCHURA: They were cervid number one.

SHEA: Dan, I like how much you’re saying cervid after just learning the word.

WANSCHURA: Well isn’t that the rule? Once you learn it, you say it to ingrain it? Besides, I could say a deer-ish thing; a hooved, deer-like creature, Patrick.

SHEA: No, that’s fine we’ll leave the hooves out of it – cervid is good. And this cervid has been through a lot. During the last ice age caribou migrated as far south as Arkansas and the Appalachians to get away from glaciers.

And after those glaciers retreated they moved north again, roaming all along the shores of the shiny new Great Lakes.

WANSCHURA: But not anymore.

SHEA: Right. They've pretty much disappeared from this part of the world – with one exception. On Lake Superior’s northern shore, caribou have hung around all this time. Barely.

WANSHURA: Get those passports out, people, because we’re going to Canada.

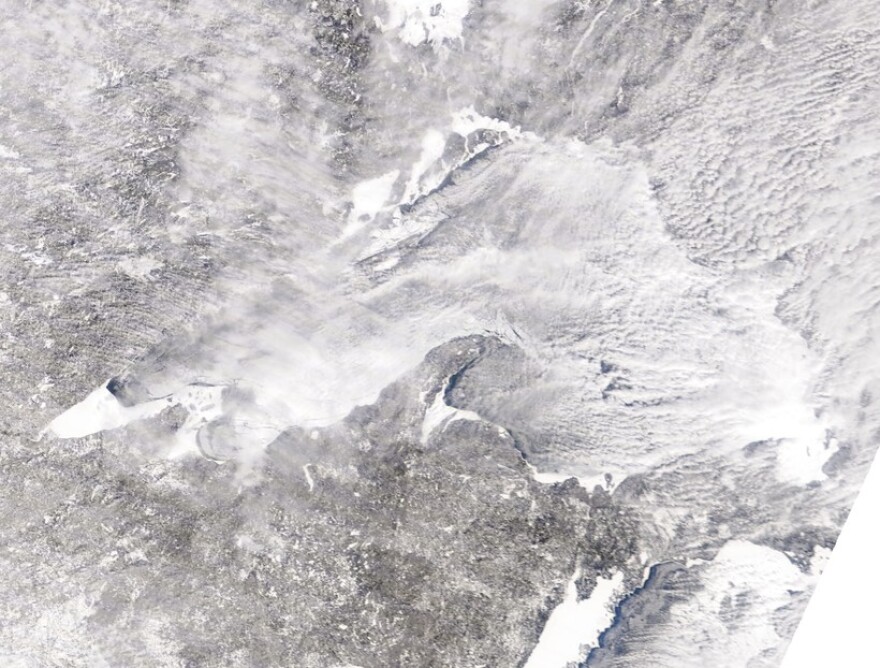

SHEA: Imagine we’re crossing the international bridge in Sault Ste Marie, and driving north along the shore of Lake Superior. Ontario is home to the largest stretch of undeveloped shoreline anywhere in the Great Lakes. It’s full of protected parks, including a series of rocky islands - perfect places for caribou to get away from predators.

Like Nancy said, caribou are really good in the snow. They’re also very agile on ice. Historically, that’s helped them cross back and forth from the islands to the mainland. That gave them the upper hand in a race with wolves.

SHEA: But in 2014, something changed. And the escape artists had no way out.

GORDON EASON: So we had one of those polar vortex winters that you probably remember being on the other side of the lake.

SHEA: That’s Gordon Eason - a retired wildlife biologist in Wawa, Ontario. He was paying close attention that winter.

EASON: Lake Superior pretty much froze over. And then on Michipicoten Island, there was three or four wolves that arrived on the ice there.

SHEA: Michipicoten island is about 10 miles from the mainland - and before the wolves showed up, it was home to around 1,000 caribou.

But then spring came fast and the ice moved out. Historically, these ice bridges formed pretty regularly. But that next winter – and the following three – the ice never came back. The caribou were stranded with a pack of hungry wolves.

Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources watched as the wolf pack grew and started picking off the caribou one by one.

EASON: So they knew as things were going along that the caribou were declining pretty rapidly. And that, you know, that 2017, 2018 was going to be the end.

SHEA: As in – the end of caribou on Lake Superior. For Gordon and many others, that didn’t sit well.

BRIAN MCLAREN: I was depressed. As were all of us.

SHEA: Brian McLaren is a wildlife biologist. He teaches at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ontario.

MCLAREN: We were flying up and down the shoreline and we couldn’t find caribou. That’s when it was clear to me that the issue was the anchors – the islands – were gone. And when they’re gone you’re not gonna find them on the mainland.

SHEA: In reality, the island population wasn’t entirely gone – but just about. By 2018 there were only 15 left on Michipicoten Island. So Brian and Gordon asked their provincial government to do something. Something more than just watching.

MCLAREN: Why would you research whether caribou can survive with wolves when you were down to the last 15 caribou on Michipicoten island? And government was not acting quickly so we pushed very, very hard.

SHEA: When Brian says we, he means a whole grassroots team of scientists and civilians, including members of several Ojibwe First Nations. And they were successful in getting the word out. They wrote letters and made phone calls to all levels of government, and informed the greater public about what was going on. Eventually, media outlets picked up the story: that Lake Superior’s last remaining caribou would be gone in a matter of weeks. Finally, Ontario took action.

WANSCHURA: Ok, what are we watching here Patrick? I see a helicopter.

SHEA: This is footage published by the Canadian Press, so thank them for the emotional backing track as well.

WANSCHURA: Wait, you didn’t pick this music?SHEA: No, no I didn’t. It’s a tear jerker isn’t it?

WANSCHURA: OK, I’m seeing a caribou blindfolded and wrapped in sort of this big, orange blanket, I guess.

SHEA: Yeah, biologists use net guns to take down the caribou. Then they sedate them, wrap them up in this bundle, load them into a helicopter, and then they fly them off the island.

WANSCHURA: So obviously they’re not quite like reindeer, or else they’d fly themselves off the island.

SHEA: (laughs) Right, yeah.

WANSCHURA: That’s wild, though. So where are these airborne caribou headed?

SHEA: Nine of them were flown over to the nearby Slate Islands. And six went to a place called – go figure – Caribou Island.

WANSCHURA: Well, that makes sense.

SHEA: And it seems like it’s working. Neither of those islands have wolves right now, and caribou numbers are growing. As of last spring, there were about 30 on the Slates, and 15 on Caribou Island.

WANCHURA: But wait. What if the lake freezes over again. Like, couldn’t this whole thing just repeat?

SHEA: Yeah, it could. And as far as we know, there still aren’t any caribou on the mainland – at least not near Lake Superior. So if wolves do make it back to the islands, that might mean another airlift..

WANSCHURA: Don’t get me wrong, Patrick, I think caribou are pretty awesome. But it does seem like so much effort for just a few caribou. I mean, there are more further north, right?

SHEA: Yeah, there are. But in Ontario, caribou have lost at least 40 percent of their range since the 1800s. That’s why they're on the province’s threatened species list. Here’s Gordon Eason again, the retired biologist for the provincial government.

EASON: So if we’re serious about protecting caribou in Ontario and getting them off of that threatened list, we need to start at the populations that are most threatened.

SHEA: Gordon says the Lake Superior population also has unique genetics, and genetic diversity is really important with any wildlife. That’s why Gordon spent his career trying to keep them around. He’s been involved with these caribou translocations, like the airlift, since the 1980s.

WANSCHURA: Wow. They’ve been shuffling these things around for like 40 years?

SHEA: Yeah, every now and then. And that’s just one part of these wild interventions going on with Lake Superior’s islands. Like for example, after they rescued the Michipicoten caribou from wolves, they moved those wolves to Isle Royale to help control an overpopulation of moose.

WANSCHURA: You know, it’s like a big game of chess on the lake. Just moving the pieces around.

SHEA: That’s a good way to put it. And experts told me that without these interventions, Lake Superior’s caribou would almost certainly be gone.

WANSCHURA: Hmm. But why get involved? To me, wolves hunting caribou – that sounds like a pretty natural process. Why are we interrupting that?

SHEA: Brian McLaren told me he hears that a lot. That this will all work itself out if the islands are just left alone. But he disagrees.

MCLAREN: This was not going to be a cycle. This was not going to be the balance of nature. And most times there is no balance of nature. And we have to acknowledge human involvement in the extinction or extirpation of species.

SHEA: Extirpation meaning the local extinction of a species - like the disappearance of caribou from the Great Lakes. Brian says if that happens, it says something about how humans are doing as land managers.

MCLAREN: If there’s a lot of evidence that we are pushing them out of their range, and at a really fast rate, they’re the canary in the coal mine. We should recognize that they represent hundreds of species that we don’t easily track. And why are we losing them?

SHEA: Why are we losing them? In part, because of climate change. Woodland caribou prefer boreal forests, that’s where they really thrive. And those forests are moving steadily northwards as the climate warms.

WANSCHURA: And then there’s the whole ice situation, right? The ice bridges are forming less frequently - that seems climate related.

SHEA: Yeah, it definitely does. And climate change was the reason Quebec’s government gave for throwing in the towel on its southernmost herd back in 2018. Officials said it was too expensive to try and save a population that was doomed anyway by global warming. But the thing is, a changing climate is nothing new to caribou. They’ve dealt with it before. Here’s Nancy Langston again, the environmental historian.

Langston: In the past, when it got hot, caribou just migrated north into the arctic. When it got cold, they migrated south.

SHEA: Nancy says, sure, climate change can affect caribou. But the real problem is development. That’s the main reason caribou have disappeared from most of their range – logging removed the habitat they need, while highways, railroads, mines and cities cut off their migration routes.

LANGSTON: And so caribou have potential if we help protect and restore migration corridors, and really think carefully about where we’re putting new roads and trails and logging infrastructure. Caribou can do fine in a changing climate if they’re allowed to migrate and find refuge from their predators.

SHEA: She says between Lake Superior and the herds further north, there’s not enough mature boreal forest right now for caribou to migrate and intermingle. So even after the airlift, the Lake Superior herd is – in a way – still stranded. A corridor could help fix that.

WANSCHURA: Okay, but what does restoring a corridor to the north really look like?

SHEA: It would look like letting trees grow. Brian McLaren says it won’t be too long before that stretch of mature forests could exist again.

MCLAREN: Forest dynamics will tell you that those corridors can be created in 40 years. That’s all we have to wait. That’s all we have to wait. So climate change is an easy out for those who want to say that we have no ability to manage the situation right now. That’s my view.

WANSCHURA: So in 40 years, will there be a corridor?

SHEA: Hard to say. I reached out to Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry for this story. I haven’t heard back. But what’s certain is that letting those forests mature does come at a cost. When Quebec gave up on its southern herd, it said it would cost $76 million dollars over 50 years to save those caribou. Most of that cost comes from lost jobs and revenue in the timber and mining industries.

Obviously, that’s a lot to consider. But it comes down to human values and economics; not certain doom because of a warming climate.

MCLAREN: We could say listen: the story is not about climate change. Through the boreal, It’s pretty clear that the ultimate decline of caribou is loss of habitat. But nobody cares. It’s not that nobody cares, but that’s the mood I’m in today.

SHEA: Brian says he doesn’t always feel this way. And I must have caught Nancy Langston in a better mood:

LANGSTON: So part of the story of the Great Lakes and of caribou is a story of restoration and hope. It’s not a story of untouched pristine things that if people come, we’ll destroy. It’s a story of how people actually can help sustain complicated ecosystems. That we really do have the option of extracting the resources we need in a respectful way that gives other species a chance to live.

SHEA: Lake Superior’s caribou still have a final stronghold on these islands, and the forests on the mainland are maturing. If another airlift is needed, Canadians will have to ask a tough question. Again.

Do we take the easy way out and blame it on the climate, or do we give caribou what they need to survive?