A popular Senator named Philip Hart had a dream to create a national park in the dunes of northern Michigan. But when he proposed the plan in 1961, it came as a shock to the people of Sleeping Bear Dunes.

“It was horrifying,” recalls Grace Dickinson, who grew up around Glen Lake and still lives there today. “It scared the people. It was like, what is going to happen to us?”

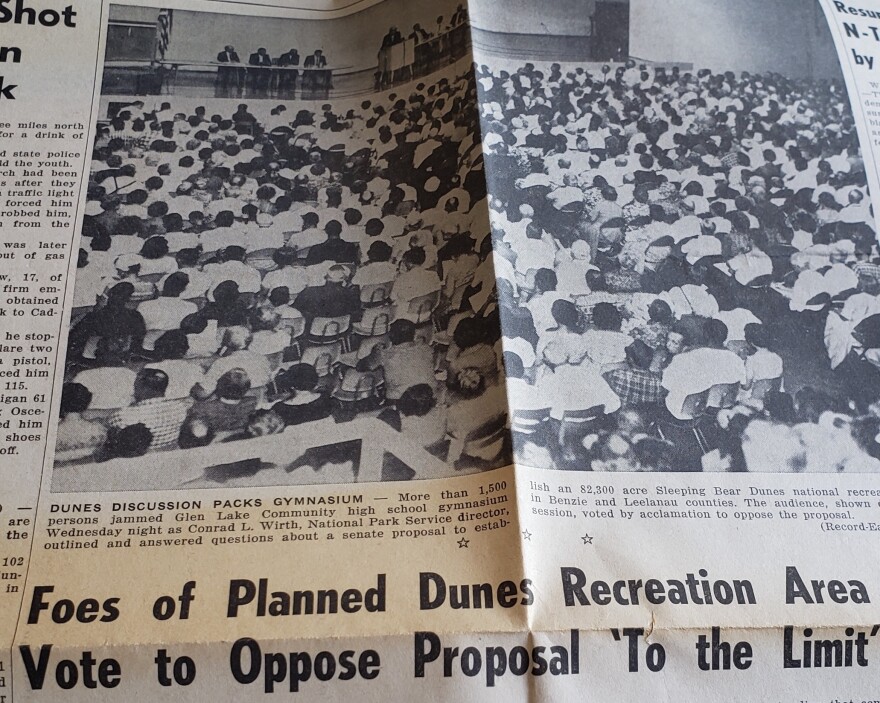

The fear that residents would lose their land and businesses was the overriding source of local opposition. Shortly after the park was proposed, over 90 percent of residents said they were against the plan, according to a newspaper survey at the time.

Dickinson remembers hearing about government representatives coming to the area. The story went that one visted South Manitou Island and stopped at a grocery store there.

“This government official comes up to the counter and puts his briefcase on the counter, in a rather loud manner, and said, ‘We are here to take your land,’” Dickinson recounts. “That just spread like wildfire. People were so upset.”

When a map of the proposed park boundaries came out, Dickinson says it crossed her family property. She remembers her father studying it closely.

“He got out his measuring tape and began pacing off various directions,” she says. He concluded that the park border would cut across their living room. “So half of our house was going to be included in the park.”

While the boundaries in the map turned out to be mistaken, Dickinson's family remained outspoken against the park plan. Her father helped found an opposition group, called the Citizens' Council of Sleeping Bear Dunes Area.

And though less of a focus,racial tensions in the 1960s also spilled over into the fight around Sleeping Bear Dunes. A survey done by a graduate student in 1962 showed many residents didn’t want more visitors, especially Black visitors.

Racial discrimination came up in letters written to Michigan representatives, says Brian Kalt, a law professor at Michigan State University who wrote a book about the park controversy called Sixties Sandstorm.

One letter Kalt found reads, “Lake Michigan shoreline is most beautiful. … It would be a good place to retire. But I would not like to have colored folks for my neighbor.”

And Kalt thinks it’s no coincidence that the main opposition group was called the Citizens’ Council of Sleeping Bear Dunes Area. At the time, the term Citizens’ Council was already in use by a group based in the Southern U.S. that advocated for segregation.

“It was an organization founded on white supremacy,” explains Stephen Berrey, a historian at the University of Michigan. “They very much pitched themselves as the ‘better class’ compared to the KKK.”

But area residents IPR spoke with say the Sleeping Bear Dunes group had no connection to the other Citizens’ Councils, and race wasn’t part of the conversation around the park. “Frankly I’m shocked and somewhat miffed that the connotation would even be associated,” says Jim Dutmers, of Glen Arbor, whose father was also a founding member of the Sleeping Bear Dunes group.

Regardless of what motivated them, those opposed to the park lost the fight. Nine years after Senator Hart proposed the idea in Congress, Sleeping Bear Dunes became part of the National Park system.

And looking back on it, many who fought so vehemently against the park are glad it’s here and the land is protected.

“When I look across the road at Alligator Hill or South Manitou or North Manitou, I can’t imagine what would have happened,” says Dickinson. “It would be just frightful.”

Others though, say it’s still hard to revisit what used to be their family’s land. There’s always the lingering question of what if it still belonged to them.