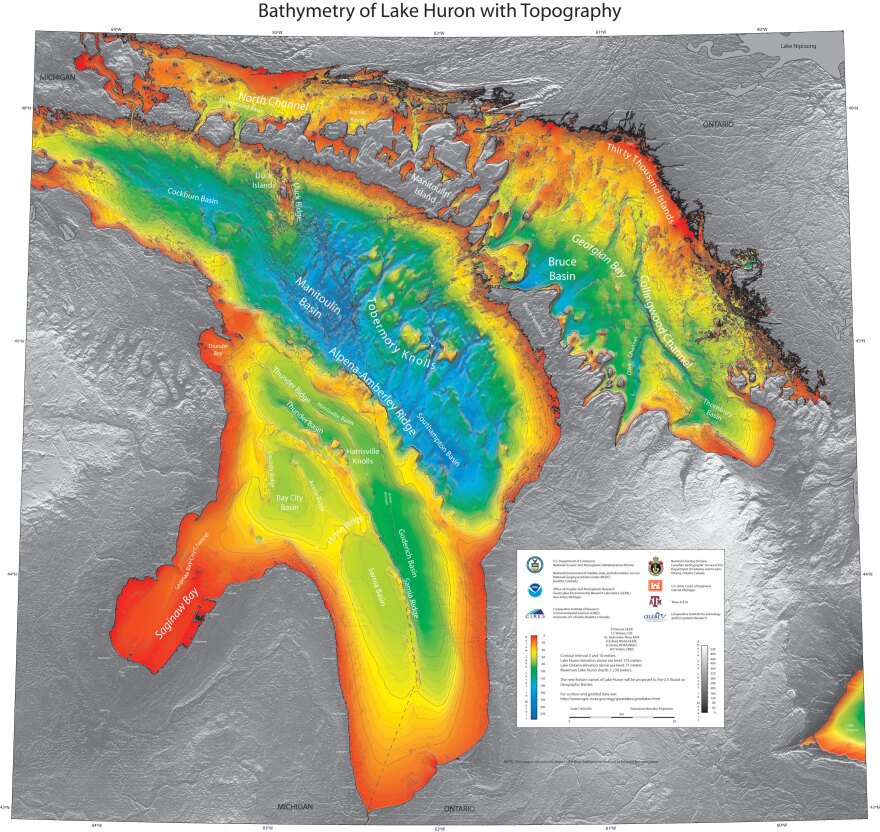

At the bottom of Lake Huron there’s a ridge that was once above water. It’s called the Alpena Amberley Ridge and goes from northern Michigan to southern Ontario. Nine thousand years ago, people and animals traveled this corridor. But then the lake rose, and signs of life were submerged.

Archaeologists were skeptical they’d ever find artifacts from that time. But then John O’Shea, an underwater archaeologist based at the University of Michigan, found something. It was an ancient caribou hunting site. O’Shea realized he needed help finding more. The ridge is about 90 miles long, 9 miles wide and 100 feet underwater.

“Underwater research is always like a needle in a haystack,” said O’Shea. “So any clues you can get that help you narrow down and focus … is a real help to us.”

That’s where artificial intelligence comes in. He teamed up with computer scientist Bob Reynolds from Wayne State University, one of the premier people creating archaeological simulations. And Reynolds and his students created a simulation with artificially intelligent caribou to help them make predictions.

CREDITS:

Host / Producer: Morgan Springer

Editor: Dan Wanschura

Additional Editing: Peter Payette, Michael Livingston, Ellie Katz

Music: Keeping Up by Blue Dot Sessions; Fluorescence and Kotoba by Nuisance; and Downtown, Happiness Is, Ice Climb, Light Touch and Vibe Drive by Podington Bear.

Sounds: Underwater Sounds by Carmsie, Lake Waves 2 by Benboncan, Water Pouring by Kyle, Waves Lapping Shore by Tom Kaszuba

TRANSCRIPT:

MORGAN SPRINGER, HOST: This is Points North, a podcast about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. I’m Morgan Springer in for Dan Wanschura.

This is a story about artificial intelligence, but it’s not about driverless cars or A.I. generated supermodels on Instagram. This is about how A.I. caribou are helping archaeologists find prehistoric sites.

JOHN O’SHEA: The artificial intelligence piece of it, I think, is just wonderful. And it opens up all sorts of possibilities for research.

SPRINGER: That’s Archaeologist John O’Shea.

O’SHEA: I’m the curator of Great Lakes archaeology at the University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology.

SPRINGER: Our story starts about 16 years ago. O’Shea was on a boat on Lake Huron, searching for signs of ancient life. He was using sonar to survey the lake bottom.

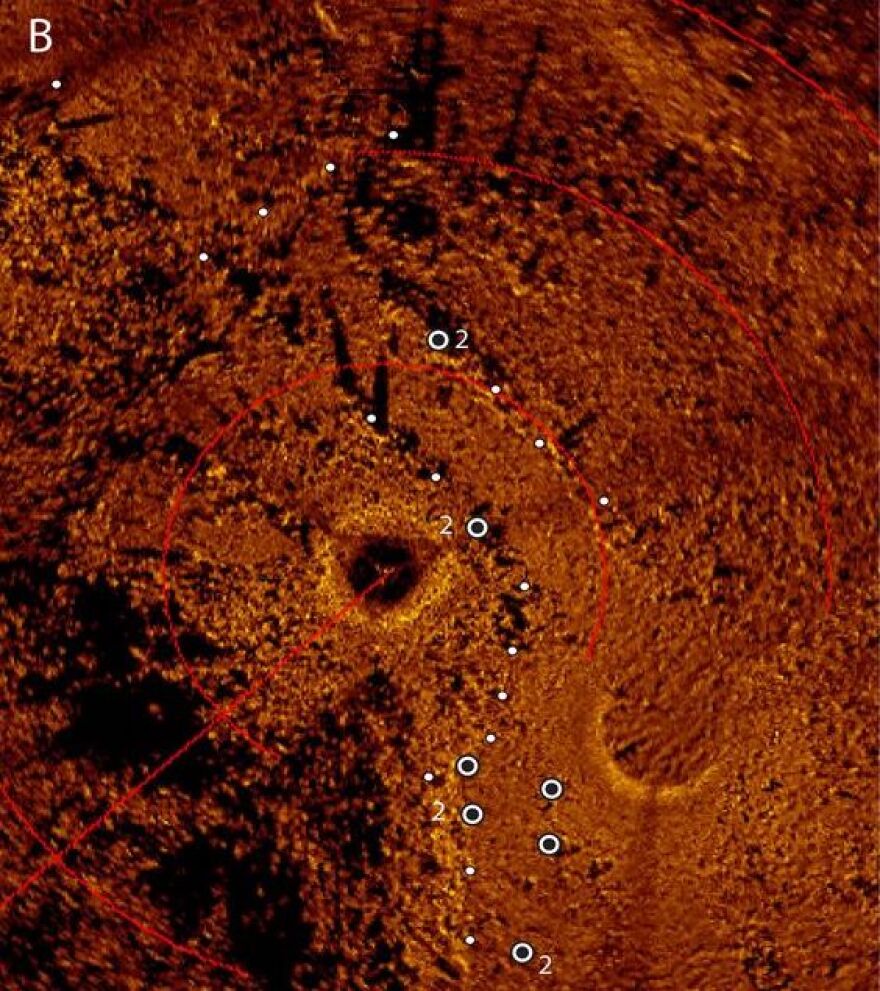

O’SHEA: Which meant driving a boat in very straight lines for hours and hours and hours in good weather and bad – to build up a mosaic image of what the bottom looked like in an area. Then once you have that, you can look at that map and say, ‘Ah, this might be something. This might be something.’

SPRINGER: Eventually, O’Shea and his collaborator did find something. It was an ancient caribou hunting site, including this line of stones put there by hunters to guide caribou to a kill site.

The site was on this underwater strip of land. It’s called the Alpena Amberley Ridge, and it goes all the way from northern Michigan to southern Ontario.

About 9,000 years ago, lake levels were lower and this ridge was above water; it was a causeway where people and animals could move.

Then the water levels rose and the land bridge was submerged. Modern day Lake Huron started taking shape.

(sounds of lapping water)

9,000 years later, no one knew if any signs of life remained, until O’Shea found that hunting structure.

O’SHEA: So we were the first ones to demonstrate that the sites were actually there and that they were preserved and could be discovered.

SPRINGER: People had found hunting structures like this in other parts of the world, but this was the first one discovered in the Great Lakes that we know of.

Now that O’Shea’s team had found one site on the ridge, they had to look for more. More sites. And actual artifacts.

The challenge was where should they look? The land bridge is about 90 miles long. It’s 9 miles wide, and it’s about 100 feet underwater.

O’SHEA: Underwater research is always like a needle in a haystack. So, any clues you can get that help you narrow down and focus the kind of places you might look at is a real help to us.

SPRINGER: That’s where artificial intelligence comes in.

ROBERT REYNOLDS: Bob Reynolds. Robert Gene Reynolds. I'm a professor of computer science here at Wayne State University. I'm specializing in the area of artificial intelligence.

O’SHEA: Bob is probably the premier person doing this kind of archaeological simulation on the planet. … And I was particularly interested in the possibility of using artificial intelligence to model where the caribou would have migrated, and Bob immediately saw this.

SPRINGER: The idea was they’d create a computer simulation model of the land bridge. And, hopefully, it would help them predict where hunting sites might be.

And so Reynolds and his students at Wayne State got to work. That’s coming up after the break…

(sponsorship message)

SPRINGER: Bob Reynolds and his computer science students at Wayne State started with the bottom of Lake Huron.

First, they create a computer model of the land bridge using its topography. Next, Reynolds says they simulate dumping water on top of the land.

REYNOLDS: Because of the slopes, you could simulate the flow of the water. … So we were able to establish, sort of, marshes.

SPRINGER: Lakes and ponds form on the virtual land bridge – even a waterfall. Then biologists help them approximate the types of plants.

REYNOLDS: And then what we had to do is to populate the landscape, and we did that developing a model of caribou.

SPRINGER: The idea was to design artificially intelligent caribou that would migrate across the landscape like ancient caribou. That would give them a sense of where hunters might have followed.

So, Reynolds and his students design a digital herd and then give them a whole bunch of instructions using computer algorithms.

Instruction one: walk.

REYNOLDS: Literally the first model, we let the herd run across the land bridge and they did not have edge perception and so they kept dropping off the sides of the bridge like lemmings, you know? And so, of course, okay, what we have to do is to put boundaries and, of course, they need to be able to perceive that. And so…

SPRINGER: So, instruction two: Perceive edges and obstacles – like digital trees, rocks and those lakes and streams.

Instruction three: go from one virtual herd to caribou that migrate in groups and can break apart.

REYNOLDS: And go off and forage, and then later on, sort of merge back together.

SPRINGER: Like real caribou do.

Over time, as each computer algorithm built on the other … the caribou movements became more and more realistic – or kind of, as Ashley Lemke points out. She’s an archaeologist on the team and a professor at University of Wisconsin Milwaukee.

ASHLEY LEMKE: The original simulation, I mean, we make jokes about it now and Bob will be upset that I say this, but the first caribou, we always laughed that they looked like they were on roller skates because they were just these really, you know, pixelated kind of rectangular caribou that didn't really walk, they just sort of rolled across everything.

SPRINGER: He won't be upset because he told me you said that.

LEMKE: Oh, okay, good.

SPRINGER: In this computer simulation of the land bridge, the intelligent, roller skating caribou migrate back and forth. Thousands of times. And with each migration, they learn the landscape a little better. They start following optimal routes, and choke points start to show up. These spots where caribou always pass through during migration.

Which means, if virtual caribou are behaving anything like real caribou, then prehistoric people might have built stone hunting structures there.

That’s where the archaeologists should go looking.

The computer scientists would give them the coordinates – longitude and latitude. And the archaeologists would go out onto Lake Huron to search – down – 100 feet underwater.

(sounds of diving underwater)

SPRINGER: Six years after John O’Shea found that first hunting structure, the research team was out on the boat in the middle of the lake. They were at this spot where the computer simulation models had predicted a choke point. Lemke says they had a new scanning sonar with them.

LEMKE: We were dropping it, we were mapping some things and didn't really see anything, didn't really see anything, and then we just dropped it, and it had this scan, and it was just this clear as day drive lane.

SPRINGER: Drive lane – another line of rocks ancient hunters placed to guide caribou.

LEMKE: It was like, ‘Oh gosh, this is an archaeological site right here.’ … All the guys were in the back of the boat, and I was like, ‘Come here, come here, come look at this. Holy cow, we found a site right now.’

SPRINGER: The archaeologists named this new site Drop 45. There they also found hunting blinds, a fireplace with burned earth and rings of rocks that may have been used to hold down the edges of tents. All remarkably preserved underwater. They’d discovered the most complex hunting structure in the Great Lakes region to date.

LEMKE: I would say when we found Drop 45 that day, everybody was ecstatic. And then similarly when we found some of the frozen trees, I mean, there's intact rooted trees on the bottom. And when divers come up, and they bring up this preserved wood that's 9,000 years old, everybody's tired. And you're like, ‘But this is really cool.’

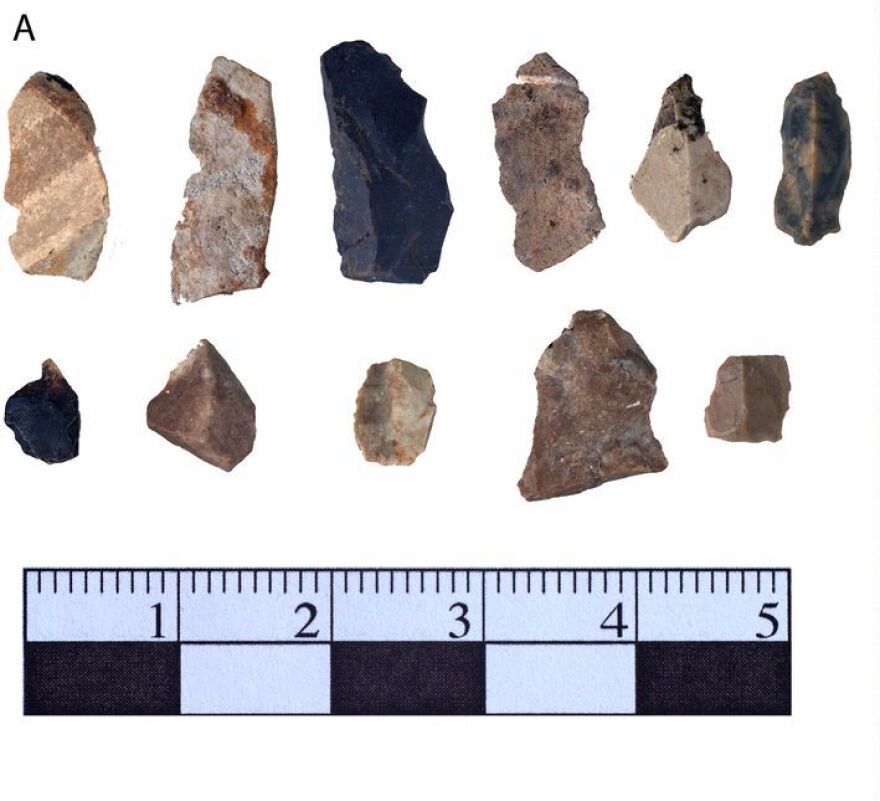

SPRINGER: They’ve found other sites and artifacts too – like pieces of obsidian that flaked off while making tools. This particular obsidian comes all the way from Oregon.

LEMKE: It's from 4,000 kilometers away. And nobody, until this project, knew that peoples 9,000 years ago were trading and exchanging for materials 4,000 kilometers.

SPRINGER: Lemke says they’ve also found unusually small tools, which is unprecedented for this time period in the Great Lakes region.

LEMKE: None of this matches the models we had about peoples in this region, which is really- it's really fascinating because then you have to go back and be like, ‘All right, well, now we have this new data, you know, what does that mean for what we thought about peoples that were living in the Great Lakes?’ You know, you kind of have to rewrite the story.

SPRINGER: The archaeologists have spent a little over a decade now searching for ancient sites on the Alpena Amberley Ridge.

LEMKE: We get asked as archaeologists, ‘How did you find a site? Or how did you know where to dig?’ And for me, I can be like, ‘Oh, well, artificial intelligence told me.’

SPRINGER: Lemke says the AI caribou have definitely helped them find sites quicker. And that’s huge – cause even 10 or so years in with the help of AI, they’ve only scratched the surface.

LEMKE: There's an image that my colleagues love using in talks that I've never used it because it makes me really depressed. But they have- it's a Google Earth image of Lake Huron, and then they have the little squares of our data – of where we've looked – and you zoom out to all of Lake Huron. You know, this has been 10 years, and we only have these little areas that we've looked.

SPRINGER: The scientists could have just continued on, trying to fill in more little squares on the Lake Huron map. But that’s not how the story ends.

Because, they decided to build a virtual reality of the land bridge so other people could experience it. Bob Reynolds and his students at Wayne State effectively took the original computer simulation and moved it over to a virtual reality. Where before, the experience was like watching a movie. Now, it was like being in the movie.

REYNOLDS: And we can see the world as a caribou would see it.

CHENCHENG ZHANG: Use your right hand.

SPRINGER: It keeps going down and is blurry.

SPRINGER: I’m in a conference room at Wayne State. And four computer science students are patiently helping me put on a VR headset. Chencheng Zhang is leading the demonstration.

ZHANG: And if you don't know how to operate…

SPRINGER: I don't know how to operate. I've never, I've never been in a–

ZHANG: So we also provide–

SPRINGER: I’ve never been in a virtual reality. But, with help, I’m launched onto the land bridge.

SPRINGER: Oh. What? Yeah. No. Wow. There’s actual terrain – like little divots.

SPRINGER: It’s a sparse landscape. Gray brown, with tufts of plants you might see in a sub-arctic climate. That’s what artifacts suggest the land bridge would have been like back then.

SPRINGER: Oh wow. This is incredible.

SPRINGER: I walk by a line of spruce trees.

SPRINGER: The trees have shadows. Wow.

SPRINGER: I’m kind of embarrassed by how many times I say wow.

SPRINGER: So, I move my head and then I– oh my gosh, the water.

SPRINGER: I look out on this virtual water where Lake Huron will one day be. And it’s truly stunning. Vibrant blues in many hues. There’s digital foam at the shoreline. And as I get closer, I can hear it.

(sound of water)

SPRINGER: There are the caribou. … They go down to eat!

SPRINGER: The caribou look good. They are definitely not roller skating. They’re walking. As I approach them–

SPRINGER: They know I’m in the way?

SPRINGER: They notice me and move away. The stone hunting structures are there too. And they’re exact – three dimensional duplicates of the artifacts. This may be the closest I’ll ever get to life 9,000 years ago. Which is truly incredible, but there’s a catch.

The computer scientists and the archaeologists sometimes have different ideas about how real and realistic this virtual reality should be.

Bob Reynolds, the computer scientist, says…

REYNOLDS: I would say because it is a simulation, it's an approximation.

SPRINGER: Was there ever a plant or something that you or your team wanted to add that John O'Shea or Ashley Lemke were like, ‘You can't add that, we don't know’?

REYNOLDS: Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha. Uh, yes. … A couple of anecdotes. One of my students decided that we're going to put in a bow and arrow. … There’s no evidence that they had bows and arrows back then.

O’SHEA: And so I kept trying to tell them, ‘No, we don't want bows and arrows in these people's hands.’ … And they wanted to elaborate, ‘What kind of bird song would there be?’ And it got to be kind of a create– sometimes frustrating, but always creative kind of interaction that we had with the archaeologists and the computer programmers talking about what this should look like and what we wanted to do.

SPRINGER: The thing is, unlike the original simulation, this virtual reality is less for research and more about educating people and getting them immersed in prehistory. Which, for the computer scientists, means this world’s gotta have enough stuff in there that it feels real. What’s the harm in some educated guesses?

Ashley Lemke gets it. But she says the archaeologists also want it to be accurate. Find a bird bone, and then we can add that bird song.

LEMKE: So, you have this balance of like, okay, how much artistic license can you have? And archaeologists do this a lot. It's like, if you think of when you see TV shows about King Tut, and they have– … we don't know exactly what he looked like. So I think where the actual product is and where the virtual world is, it's kind of in the middle.

SPRINGER: Somewhere between accurate and a world that feels real.

Bob Reynolds cares about accuracy. And he says he does tend to be careful about how much artistic license they take.

REYNOLDS: We can recreate a past that never was there. And we can produce a prehistory that has no real basis in reality. But we could do that. And the question is, why would … someone want to do it? And what would be the issues if that happened?

SPRINGER: It would be a world where we can no longer tell what’s real and what isn’t.

Did a campaign create that political ad or did AI make it? Is that Jay-Z rapping in that song or did AI generate his voice? Did a journalist write this story? Or was it Chat GPT?

When I put on the VR headset, I do want it to be accurate, and I want it to feel real. But, most of all, I want to know what I now know. Which is that this virtual reality is a very cool approximation of prehistoric life on the land bridge. It’s about as close as I’ll ever get to time travel.