In the fall of 1960, Prince Akihito of Japan took a whirlwind tour of the U.S. to celebrate 100 years of diplomatic relations between the two countries.

Akihito stopped in Chicago for only 21 hours, but Shedd Aquarium was at the top of his sightseeing list. He got his wish. At the aquarium, Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley presented the prince with a gift of friendship: 18 bluegill, the Illinois State Fish.

“The newspapers were super proudly saying that the fish would go home to the imperial pond in Tokyo,” said science journalist Christian Elliott, who reported on Akihito’s visit for National Geographic in 2022.

Prince Akihito did almost exactly that: He read a goodbye speech, packed up his fish and went home. But what happened next would kickstart an ecological catastrophe, changing the underwater world of Japan forever.

Credits:

Producer: Ellie Katz

Host: Dan Wanschura

Editor: Morgan Springer

Additional Editing: Dan Wanschura, Peter Payette, Michael Livingston

Translation and Additional Production: Frank Walter

Special Thanks: Jeannie Shinozuka

Music and Sounds: Silver Lanyard, Tiny Putty and Lost Stage by Blue Dot Sessions and Footswitch Sound by Nightwatcher98

Transcript:

DAN WANSCHURA, HOST: The plane touched down on a Tuesday afternoon. Crowds of Chicagoans gathered around, cheering, waving flags. Then, the door opened. And there he stood.

CHRISTIAN ELLIOTT: The Japanese Emperor, who was then Crown Prince Akihito. He was 26 years old, so just a young guy.

WANSCHURA: That’s journalist Christian Elliott. Decades after Akihito and his wife landed in Chicago, Christian reported on their trip for National Geographic.

(archival newsreel sound)

AMERICAN NEWSCASTER: At the White House: A glittering state dinner with the President and First Lady playing hosts to Prince Akihito of Japan and his princess, Michiko…

WANSCHURA: It was October 1960. The prince and princess were on a whirlwind tour of the U.S., from Honolulu to New York to Washington, D.C.

(archival newsreel continues)

NEWSCASTER: … for this occasion, Princess Michiko substitutes for the traditional Japanese kimono a western evening dress.

WANSCHURA: They were there to celebrate a century of U.S.-Japan relations. And they only had 21 hours in Chicago.

ELLIOTT: I mean, the prince is, like, meeting with the governor of Illinois, and he's meeting with the then-Mayor Richard J. Daley. They go to a fancy dinner, they're in a fancy hotel, but the whole time what Akihito really wanted to do was visit the Shedd Aquarium.

WANSCHURA: Akihito – like his father before him – was a bit of a fish fanatic, and would later become a published scientist on the subject. And he just wanted to see some fish he had never seen before.

So Prince Akihito and Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley took a trip to the aquarium.

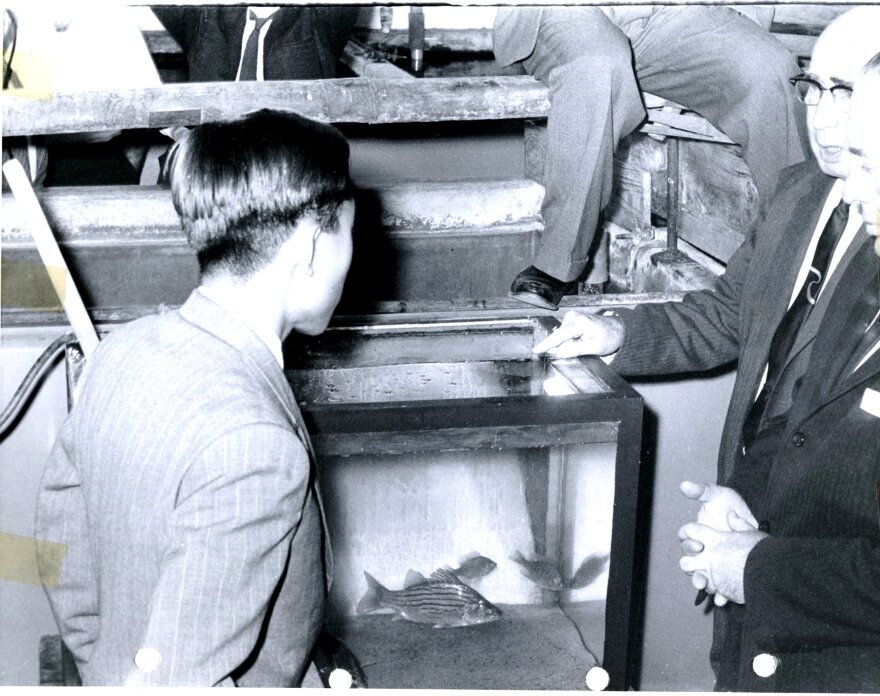

ELLIOTT: There's these photos of Akihito, like with his business suit on and these, like, giant glasses and he's just staring into fish tanks at the Shedd Aquarium. And Daley decided to give him 18 bluegill as a gift of friendship because they were the Illinois State Fish. In some accounts, at least, he scooped the fish out of the aquarium tank at the Shedd himself, and gave them to the prince. And the newspapers were super proudly saying that the fish would go home to the Imperial pond in Tokyo.

WANSCHURA: And Akihito did almost exactly that. He read a goodbye speech, packed up his fish and went home. But what happened when he got back would change the underwater world of Japan forever. This is Points North. A podcast about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. I’m Dan Wanschura. Today, we take a look at one species the Great Lakes exported. Producer Ellie Katz follows 18 little bluegill from the Windy City to Tokyo. That’s right after the break.

(sponsor messages)

ELLIE KATZ, BYLINE: Out of those 18 bluegill, 15 survived the trip to Japan. And people were pretty excited about them.

KATSUKI NAKAI: So in the beginning, in the 1960s, bluegill was a celebrity.

KATZ: That’s Katsuki Nakai. He’s the retired curator of the Lake Biwa Museum in Shiga Prefecture. He’s studied fish in Japan’s Lake Biwa for over 30 years, including bluegill.

NAKAI: At first, we tried to establish a technique of aquaculture for bluegill.

KATZ: For a while, it seemed like aquaculture, trying to raise bluegill for food, might work. The Fisheries Agency renamed bluegill “the prince fish” in Akihito’s honor. But after a few years, it became clear that breeding them wasn’t viable. So they gave up the project.

NAKAI: In the latter half of the 1960s, bluegill was almost a forgotten species.

KATZ: But Katuski says something really started to change in Japanese culture in the 1970s: American-style bass fishing became incredibly popular. Largemouth bass were introduced to ponds across the country, and bluegill were introduced alongside them as their bait.

NAKAI: So both fish established almost nationwide distribution and became a very popular target of fishing.

KATZ: Largemouth bass thrived and decimated native fish populations. In Lake Biwa, some native fish species completely disappeared. But as the bass finished off every last morsel of their favorite foods, their numbers started to decline, and bluegill seized their opportunity. With fewer bass to prey on them, and with a less picky appetite, bluegill numbers exploded. Like largemouth bass, bluegill pushed even more native species closer to the brink and threatened commercial fisheries. (In Lake Biwa, especially, that’s a problem. Because Lake Biwa isn't just any old lake. It's almost like a Great Lake of Japan ... it's the country's largest freshwater lake… and one of the oldest in the world. Several fish species there are found nowhere else.) But by the early 2000s, in certain areas of Biwa, 90 percent of the lake’s fish population was bluegill. And bluegill aren’t the only ones who’ve moved in.

NAKAI: Now, in Lake Biwa we can find many North American species: bluegill, largemouth bass, red swamp crayfish, and American bullfrog.

KATZ: Katsuki says the underwater world of Lake Biwa, and almost all Japanese freshwater ecosystems, have been Americanized. And all across Japan, they’re trying to slow or entirely reverse what’s happening.

KATZ: Andrew Kustodowicz has seen these efforts firsthand.

ANDREW KUSTODOWICZ: In Japan, the Ministry of the Environment has this big list, it's like the worst invasive species list. It reminds me of a criminal list, you know, like a wanted list almost.

KATZ: Andrew studies the environmental history of Japan through sport fishing, specifically American sport fish introduced to Japan, like bass and bluegill. He says many of these species are seen as invaders waging a war on Japanese ecosystems. And that people have come up with all sorts of ways to get the message across, ranging from toys in a vending machine:

KUSTODOWICZ: You get one of six different invasive species, little miniatures, and it has a red circle with a slash, you know, like the stop sign.

KATZ: …to the shores of the lakes themselves:

KUSTODOWICZ: There's particular, like trash cans, sometimes set up by prefectural governments on the side of lakes that, you know, if you catch a foreign species, you're just supposed to throw it away in this trash can to be disposed of.

KATZ: There are laws that make it illegal to have these animals. And for a long time, fishermen on Lake Biwa could earn a bounty for hauling in as many bass and bluegill as possible. A lot of these methods seem to have worked; bluegill numbers in Lake Biwa are far lower than they used to be.

Here in the Great Lakes, we do a lot of the same exact things to stop invasive species, and then some: Electric shock barriers to prevent invasive carp from entering Lake Michigan. Pesticides to kill sea lamprey. Divers to scrape zebra mussels off by hand. We’re right to worry about some of these new species – their arrival has fundamentally altered the ecosystems we love. But sometimes we forget we’re not the only ones dealing with this. Invasive species are a global problem – from the Great Lakes, to Japan, and everywhere in between. And we contribute to that problem. But there’s this weird thing we do: We talk about these species like they are foreign invaders and we are under attack.

(montage of newsreels)

NEWSREEL 1: “It’s an invasion from coast to coast – from Africanized killer honeybees in the southwest, to South American nutria in Louisiana, to the spread of the Burmese python in the Florida Everglades – all part of a scary trend.”

NEWSREEL 2: “...the worst fish in America: Asian carp.”

NEWSREEL 3: “...but this little bug is actually an ecoterrorist.”

NEWSREEL 4: “...is all part of a never ending battle with the silent invaders.”

NEWSREEL 1: “You make it sound like we’re under attack everywhere.” “We are under attack everywhere.”

KATZ: There’s the issue of this getting tied up with the history of racism and xenophobia in the U.S. (That’s its own story.) And then there’s the whole “invaders'' narrative, which gets one really important detail wrong.

EL LOWER: Invasive species don't really have a will of their own.

KATZ: That’s El Lower. They study how we communicate about aquatic invasive species for Michigan Sea Grant.

LOWER: They’re plants and animals and other organisms that don't intend to be as inconvenient as they are. They certainly don't intend to, you know, maliciously form battle plans and come over here and suck up nutrients that native species eat, or crowd out other aquatic plants.

KATZ: Casting invasive species as villains deflects responsibility from us. We’re the ones who moved them away from their home in the first place, and we’re just as complicit in changing the landscapes around us.

KATZ: Taking responsibility, though, gets tricky when invasive species hitched a ride around the world on international ships or trendy ornamental plants. But there is one person – one former emperor – responsible for taking bluegill from the Great Lakes to Japan. Akihito. (Okay, maybe there’s two people: Akihito and Mayor Daley of Chicago, who gave Akihito the fish.) But Daley is dead. And Akihito is almost 90 now. Yet every single bluegill in Japan – and there are now millions upon millions of them – can trace its genes back to those 15 original fish he brought back from Chicago. And in 2007, Akihito said he regretted it.

(Former Emperor Akihito speaks in Japanese)

KATZ: In this speech, Akihito says: “My heart is saddened that the bluegill I brought from America fifty years ago have caused such damage to the ecological environment of Lake Biwa. We had high hopes for them to become a new staple food when I gave them to the Fisheries Agency for study. I’m deeply troubled by how it turned out.”

It was a rare thing to do. Not many emperors publicly acknowledge their mistakes. But Katsuki Nakai, the researcher at Lake Biwa, says he had this reaction when he heard the apology:

NAKAI: Oh! It's history. Nobody predicted its invasiveness in Japan.

KATZ: It’s history. Nobody – not even Akihito – could’ve known what would happen. Bluegill symbolize something totally different now in Japan, so different that it’s easy to forget what they originally were: a gift of friendship. A symbol of 100 years of diplomacy between the U.S. and Japan that against all odds was still going, even after a bloody war, incarceration camps and atomic bombs. After all that, 15 little fish managed to survive a flight across the ocean and thrive.