We’ve all heard about lead before, and its dangerous side effects. Long-term exposure has been linked to brain damage and organ failure in humans. It’s equally as devastating in wildlife.

A 2022 study finds that about half of adult bald eagles in North America have chronic lead poisoning. Raptor centers around the region continue to take in birds with severe symptoms.

Experts point to lead bullets left behind by hunters as a leading cause for this trend. So, some hunters and ecologists are trying to change that.

Subscribe and listen to Points North wherever you find podcasts: Apple | Spotify

Credits

Producer: Michael Livingston

Host: Dan Wanschura

Editor: Morgan Springer

Music: Run To Life, One Man Book, Hans Troost

Special thanks: Wildside Rehabilitation Center, Skegemog Raptor Center, University of Minnesota Raptor Center

Transcript

DAN WANSCHURA, HOST: This is Points North: A show about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. I’m Dan Wanschura. And this time, I have someone really special for you all to meet.

DARLENE SMITH: Can you feel the heat under there Jonah? Are we at a good temp?

JONAH WOJNAR: Oh yeah, it’s warm.

WANSCHURA: No, not them. Let’s try again.

(Silence, room noise)

Okay. He’s not making any noise. But these two volunteers are checking in on their patient. A beautiful, young bald eagle.

WOJNAR: This is Apollo

SMITH: Like Apollo 13!

WANSCHURA: That’s Jonah Wojnar and Darlene Smith from the Wildside Rehab Center. Apollo still has patches of brown feathers on his head, which means he can’t be more than five-years old. But right now he’s slumped over in his enclosure. He sighs deeply and cracks open his bright yellow eyes. He doesn’t have the strength to make any noise right now.

That’s because Apollo has poisonous levels of lead in his blood. We’ve all heard about it before: lead and its devastating effects.

(News clips highlighting lead contamination dangers from around the region)

WANSCHURA: Long-term exposure has been linked to brain damage and organ failure in humans. It’s equally as devastating in wildlife.

The problem is, lead is in a ton of things: old paint, water pipes, car exhaust. We're going to explore how lead is poisoning and killing bald eagles at alarming rates. And reporter Michael Livingston follows Apollo to see if he’ll survive.

Today’s episode, Taking the Shot to Save the Eagles.

MICHAEL LIVINGSTON, BYLINE: The bald eagle is America’s bird – a symbol of freedom. But there was a time we nearly wiped them out. In the 1960s, government scientists found only about four hundred nesting pairs of bald eagles in existence. That’s because the eagles were being killed by a chemical compound called DDT, which was being used as a pesticide following World War II.

But when DDT was banned, bald eagles made a remarkable comeback. This national symbol now numbers over 300,000 according to federal data, stretching from New England to Alaska.

Apollo is part of this amazing recovery, but on January 11th, he was found on the ground underneath some power lines in southern Michigan. He was rushed to a vet then transferred to Wildside Rehab.

Apollo’s still not making any noise. He’s in a baby crib at the rehab center that’s been converted into an enclosure.

WOJNAR: He came in, he cannot stand, he's able to move one leg, the other one, he doesn't seem to be able to move at all. And then he has what our vet thinks is an old injury where the eye was punctured, and it's scarred over.

LIVINGSTON: He’s likely blind in that left eye.

WOJNAR: And then the lead poisoning.

(laughter)

LIVINGSTON: If you can’t tell, that’s a nervous laugh.

There’s a lead level that would normally hospitalize an eagle; Wojnar says Apollo has twice that. The lead is likely causing a lot of Apollo’s weakness and balance issues. But weakness and balance aren’t the only way lead can attack the body. Depending on levels, lead can carry a lot of negative impacts.

VICTORIA HALL: It's one of the saddest things we see because these birds are beautiful, healthy, strong birds. And it’s lead that brings them basically to the ground.

LIVINGSTON: Victoria Hall is the director of the Raptor Center at University of Minnesota

(Sounds of weak, feeble eagle)

LIVINGSTON: This eagle was filmed as part of a collection of videos by the raptor center. Those are likely cries of confusion as the lead attacks the nervous symptom. Videos of other lead-poisoned eagles show them spinning their heads around rapidly. Their eyes blink uncontrollably. It almost looks like they’re drunk or got hit in the head.

HALL: If it had enough lead, could be seizing, unable to stand, unable to see; it might be vocalizing.

LIVINGSTON: The University of Minnesota is a national leader in studying this trend. The amount of times Hall says she’s seen lead poisoning is astronomical.

HALL: Even after decades of work on this issue, we’re still seeing 80-90% of the bald eagles that come into our center, showing some level of lead in their blood.

LIVINGSTON: We don’t know how many eagles are dying because of this on a national scale, but Hall says almost a third of bald eagles admitted to the raptor center for lead poisoning die from their symptoms.

A 2022 study published in the journal Science, estimates more than half of adult bald eagles have chronic lead poisoning. The scientists estimate lead exposure could reduce the bald eagle’s growth rate by 4% per year.

HALL: We brought Eagles back from the brink once, but we have to constantly be on alert for threats that could hurt their populations again. And lead is proving that it's prevalent enough in these birds, it could have a population impact.

LIVINGSTON: There are a number of solutions to address the lead problem. One of them is treatment, like what Apollo is getting at Wildside right now.

WOJNAR: So right now I’m feeling for his keel bone which is that center bone, so it’s the breast bone. I’m going to go off to the bird’s right side. And I'm just gonna go right into the muscle here.

LIVINGSTON: They’re injecting Apollo with calcium EDTA. This compound will grab on to molecules of lead and filter it through his kidneys. After that, he just pees it out.

To help with that, Apollo is on an all-liquid diet that has to be injected through a tube down his throat. He doesn’t like that part.

WOJNAR: Oh! We’re getting feisty now!

LIVINGSTON: As Wojnar tries to insert the tube, Apollo resists, moving his head around. It’s actually the most he’s moved yet. This treatment can sometimes get lead levels back down to almost zero. For other birds though, the damage to their nervous system or vital organs could lead to death.

The other solution to the problem is taking lead out of their diet entirely. That’s a lot harder.

Birds are poisoned from plenty of sources: dust from lead paint chips, leaded gasoline in soil, microtrash from landfills. But the majority of research continues to point to one huge source: lead bullets left behind by hunters. The study I mentioned earlier, identified a dramatic uptick in severe lead poisoning around hunting seasons.

This is how lead gets into the birds: imagine a hunter goes out into the woods and legally shoots a deer with a fully-lead bullet. On impact, something happens.

HALL: Lead is very soft metal, when it hits something, it tends to fragment.

LIVINGSTON: These fragments travel up to 18 inches throughout the carcass, sometimes the size of a grain of sand. The hunter will either gut the deer right there or take it back home and leave all those gross bits outside. Then, a bald eagle eyes the gut pile from the top of a tree.

HALL: That is an incredibly rich and nutritious meal for a bald eagle.

LIVINGSTON: It eats away, as quick as it can, and as much as it can.

HALL: But unfortunately, as they feast on that gut pile, they also can ingest lead.

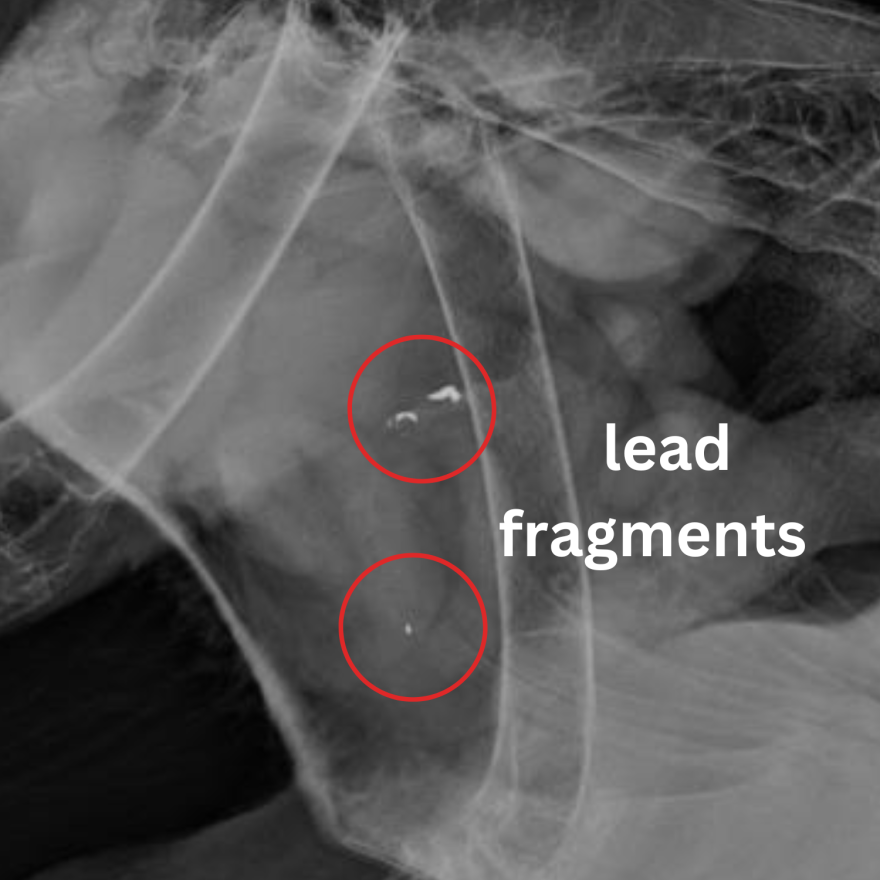

LIVINGSTON: We don’t know if this is how Apollo got poisoned. By the time Apollo had his X-rays taken, there was nothing there – any large chunks of lead in his stomach would have already been passed.

Lead paint is banned, lead infrastructure is being phased out. We know the banning of DDT helped bald Eagles recover from near extinction. So why do we still have lead bullets?

CHAD THOMAS: Lead is tradition.

LIVINGSTON: That’s Chad Thomas, an Outreach Coordinator at the Institute for Wildlife Studies.

THOMAS: There are bullets that date back to the 1940s, 50s – that are still extremely popular on shelves today. So the tried and true reliable bullet that kills that my grandfather used and then my dad used and then when I was learning to hunt, he bought it for me because he goes, ‘this is a great bullet.’

LIVINGSTON: That may have been the case when Thomas was growing up. But now, his whole job is working with hunters to help them understand why lead ammo is dangerous. He isn’t calling for an outright ban, but he says hunters should work to greatly reduce the number of lead bullets they use.

THOMAS: We are conservationists, we are stewards of wildlife, and we're naturalists. We care about landscapes and wildlife, not just game.

LIVINGSTON: There are barriers to non-lead ammo, though. One of them has been price, historically. Copper is a more rare material and manufacturing costs are typically higher.

THOMAS: My first box of non lead ammunition cost me $70 and that was in 2008. In comparison, my lead box of ammo cost $22. So that was a massive difference. And to a starving community college, part-time minimum wage kind of guy that really hit me in the budget hard.

LIVINGSTON: But Thomas says that’s changing. With more companies producing non-lead rounds, the competition has reduced prices to be nearly equal with lead. But the other barrier is, some hunters just want lead bullets and disagree with the research that links them to poisoning eagles and other scavengers.

The National Sports and Shooting Foundation takes that stance and says this is just a ploy to vilify hunters. We reached out to them for an interview but weren’t able to get a comment in time for this episode.

But in a press release the organization says, “If hunters’ use of traditional ammunition was adversely impacting bird populations, raptor and bald eagle numbers wouldn’t be soaring, as they have been.”

And yes, on a population scale, the number of bald eagles is still increasing – just more slowly. But researchers say that’s only part of the story.

JAMES MANLEY: I think when you have people that don't know there's a problem or there's a risk, then, you know, I think it's a challenge.

LIVINGSTON: That’s James Manley. He runs a small, fairly new raptor center in Traverse City, Michigan. Earlier this month, Manley had to euthanize a bald eagle with incurable levels of lead in its blood. X-rays showed there were lead bullet fragments in its stomach.

MANLEY: It's easy to get angry. But I think if I get angry, and go after people that maybe are contributing to the problem, instead of trying to work alongside them, I'm going to continue to deal with this.

LIVINGSTON: The real solution, Manley says, will come from educational outreach instead of polarizing bans on lead. He started visiting schools and libraries last year to help spread the word.

MANLEY: Just in our last three social media posts, comment after comment is, ‘How are they getting lead poisoning? How are they getting lead poisoning?’

LIVINGSTON: He says, many hunters don’t realize the damage lead bullets are causing. He hopes as more hunters become aware, demand for non-lead alternatives will increase.

About a week after I met Apollo, he’s made a lot of progress. He now wears a harness to help gain some mobility in his legs. He still gets his lead poisoning treatment every day but Wojnar and Smith say he’s expected to recover from that. He even got to eat some solid food for the first time in a week.

WOJNAR: You're definitely hungry.

LIVINGSTON: His other injuries could keep him at Wildside for another couple of years.

Then hopefully, back to the wild.