Ninety percent of North America’s surface freshwater is in the Great Lakes. So every now and then, the Great Lakes are proposed as a solution to drought in the American West. There’s been speculation about piping water to Idaho, Phoenix or Las Vegas.

But some say the more immediate danger is commodifying water, including trading water on a futures market.

“I think water is a human right, and I don’t think we should be speculating or trading in human rights,” said Dave Dempsey, author of “Great Lakes for Sale.”

Dempsey has more than 35 years of experience as an environmental policy analyst, working for the Michigan Environmental Council, the Great Lakes Fishery Commission and the International Joint Commission.

Dempsey published “Great Lakes for Sale” in 2009, but he released an updated edition last year in reaction to recent diversions of Great Lakes water in Wisconsin.

“That's a taste of what's to come,” Dempsey said. “And these diversions are legal under the compact if they're within Great Lakes states,” adding that such legal diversions are a concerning loophole in the Great Lakes Compact.

Dempsey said that a new market for trading California water futures through the Chicago Mercantile Exchange Group is another troubling development that prompted the book’s updates.

But some economists say the trading of water futures is nothing to fear.

“My view is not necessarily that they're good or bad,” said Heidi Schweizer, an assistant professor of agricultural and resource economics at North Carolina State University. “It's a financial instrument that has a specific purpose, and people are only going to use it if they think it might help them manage risk in some way.”

Schweizer co-authored an article on the topic with Ellen Bruno, an assistant professor in the same field at University of California, Berkeley. According to Bruno and Schweizer, water futures act more as a form of insurance for water users than a market for the exchange of actual water.

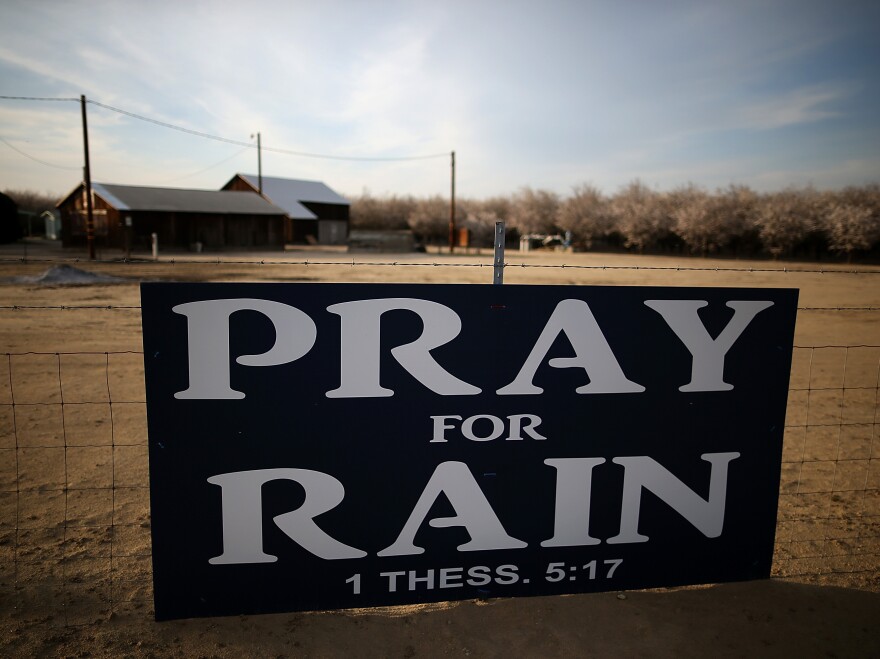

“In the California context, we often think about farmers,” Bruno said. “Given the uncertainty associated with water supplies in California, there's a natural water price risk.”

Bruno said participating in a water futures market could help farmers, municipalities and other water users to manage that risk, especially as precipitation becomes more variable due to climate change.

“To lock in the price for water eliminates future uncertainty and helps farmers make planting decisions,” Bruno said.

Dave Dempsey said he agrees the new market isn’t a cause for panic, but that it sets an ethically questionable precedent.

“I see it as part of a trend towards treating water as a commodity — as something that has a market value that can be quantified and turned into profit or loss,” Dempsey said. “I totally disagree with that premise.”

Schwiezer and Bruno said that despite how one feels about trading water futures, it seems unlikely to take off anytime soon due to a lack of investors in the market’s first year.

But Bruno said that — if implemented correctly — a water futures market could be a useful tool.

“If water as an input to production and agriculture isn’t priced correctly, it will lead to the misuse of that resource and exacerbate water scarcity issues,” Bruno said. “There are ways we can use market instruments to improve the price and allocation of water.”