Lyme disease is increasing in the Upper Midwest. The illness is caused by a bite from an infected black-legged tick.

But the disease can be hard to spot. If left untreated, it can spread to other parts of the body and cause arthritis and nervous system problems.

Are doctors prepared to diagnose and treat a rising number of Lyme infections?

Credits:

Host: Dan Wanschura

Reporter/Producer: Taylor Wizner

Editor: Morgan Springer

Music: Mike Cavenaugh, Landsman Duets, Caslo

Transcript:

DAN WANSCHURA, HOST: Cindy Miner had this dream for her retirement. She would move near Lake Michigan. And train her 150 pound Newfoundland dog to rescue drowning swimmers.

CINDY MINER: With all the lakes and the drownings that are here I thought this would be something I could do to present to the Coast Guard rescue station in Traverse City.

WANSCHURA: But her dream was cut short when she developed extreme exhaustion. Some days she can hardly move. And she hasn’t been able to train her dog Sunshine.

MINER: I can’t walk him more than half a block without getting tired. And he’s rearing to go.

WANSCHURA: Doctors have offered her few answers. That was until she got the diagnosis that finally made some sense. The culprit was a tiny bug.

You’re listening to Points North, a show about the land, water and inhabitants of the Upper Great Lakes. I’m Dan Wanschura.

Cindy lives in a pine filled subdivision outside Traverse City, Michigan. Reporter Taylor Wizner met her there.

TAYLOR WIZNER, BYLINE: Cindy’s home is airy, with a cream colored interior and floral patterned furniture. To anyone’s eye it’s tidy, but Cindy sees all the chores she doesn’t have the energy to do. She apologizes for not vacuuming.

MINER: I get to where I can’t do my paperwork. I can’t keep the house clean.

WIZNER: Cindy wasn’t always this tired. She could spend all day outside gardening and walking her dog.

MINER: I was taking hikes and jogging and bicycling for 30 miles and had no problem so this is a total different life for me.

WIZNER: She went to four or five doctors.

MINER: It was things like fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue. Things that to me didn’t seem to have a real cause or real reason for them happening.

WIZNER: Cindy didn’t accept the doctors’ explanations. She asked one doctor if they could run more tests, including for Lyme disease — a tick-borne illness.

MINER: The reply that I got was, oh no, no it’s nothing like that. It was kind of, you’re getting older, maybe you’d better look into assisted living. And I thought, wait a minute, I’m just getting ready to travel and see the world.

WIZNER: In the U.S., Lyme disease is mainly found in the Northeast and Upper Midwest. The infection comes from tiny black-legged ticks, also called deer ticks.

Nymph ticks can be so small you barely spot them, but they balloon when engorged with your blood. Here’s how it happens, the tick bites you, and if it's infected, it can pass the bacteria to you.

Since it was identified in Connecticut in the early 1970s, Lyme has spread to the Upper Midwest, especially forested areas in Wisconsin and Minnesota with some pockets in Michigan.

A number of factors including climate change and reforestation have made the region more hospitable to ticks, many carrying the bacteria with them.

The primary way physicians diagnose the disease is by spotting a bull's-eye rash. But some experts say a rash doesn’t always appear, or isn’t identified in some people who have Lyme.

Symptoms include fever, chills and muscle pain. And if untreated, it can cause arthritis and affect the nervous system. Because the symptoms present in a number of different ways, some doctors estimate a lot of Lyme cases are missed.

Take Chris Sack, who lives in northern Michigan. One day last year he went to the ER with a horrible fever and chills. They assumed he had meningitis.

Days later, at a different hospital downstate doctors tested him for Lyme, and it came back positive. Chris says the hospital Up North just didn’t know.

CHRIS SACK: They didn’t identify it. They just hadn’t had experience with it up here.

WIZNER: His infection cleared up with antibiotics, but he still has neurological issues.

Barbara Klein had a similar story. She had searing back pain when she was on vacation in northern Michigan and went to the local hospital. She left without a clear explanation. Later, when the pain became unbearable, she went to a hospital near her home.

BARBARA KLEIN: And it wasn’t until I’d been in the hospital for seven days that the neurologist came back and asked me, is there any chance that you’ve been camping this summer?

WIZNER: She just spent 14 weeks at a rustic campground. After a week of tests, doctors finally figured out it was Lyme.

KLEIN: I can’t really blame them for not thinking of it. I guess it’s, it can present in many different ways. And the symptoms can be confusing. And it’s probably not the first thing doctors are thinking of. But I think it’s rising in their awareness of Lyme disease.

WIZNER: In the last two years, Cindy Miner’s symptoms got worse, and desperate, she went to more doctors for advice.

MINER: They don’t hear all of the things that are going on and if you start listing a lot of different symptoms that you’ve got they tend to see it as you’re just fabricating, or that you’re a woman and that you just tend to complain more.

WIZNER: Cindy started looking into alternative medicine and met a naturopath in Traverse City. Doctor Andrea Stoecker spent a few hours with Cindy doing a detailed medical history. Lyme came up. Cindy thought back to a time when she took her dog on a hike.

MINER: He got back in the car and there were ticks all over him. He was just covered with ticks. And I found them on myself and I found them on the seat and on the floor. And I just thought, woah we really hit a bad spot there.

WIZNER: The naturopath decided to order antibody tests for Lyme disease. And Cindy’s initial hunch was correct: she tested positive. Dr. Stoecker based her initial assessment on emerging research she’s been following.

ANDREA STOECKER: We aren’t given a lot of training in it to be honest in medical school and it's not covered in our continuing medical education. The lack of knowledge about how chronic Lyme presents and how to treat it. You really have to spend a lot of your own time learning about it.

WIZNER: She only recently started treating patients with chronic Lyme.

STOECKER: There was nobody for me to send them to so it was just up to me to figure out how to help them.

WIZNER: Dr. Christopher Ledtke has a slightly different perspective. He’s an infectious disease specialist at Munson Medical Center, the largest hospital in northern Michigan, and says doctors are looking for Lyme more now.

CHRISTOPHER LEDTKE: Usually there’s a low threshold to call an infectious disease specialist and then we can talk the provider through how to look for this and how to treat it. But we certainly need to continue communication with our local providers about looking for this.

WIZNER: Cindy Miner’s diagnosis is controversial. Most doctors, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, believe Lyme is a short-term disease. It can last up to six months, and if caught early, can be eliminated from the body with antibiotics. They’re skeptical of chronic Lyme.

The CDC recommends taking two tests that measure antibodies to determine if a patient has Lyme. Both tests have to come back positive. Dr. Ledtke, who we just heard from, says some doctors misread one of the tests.

LEDTKE: That is very difficult to interpret to be honest with you and it’s often misinterpreted.

WIZNER: But another doctor, Steven Phillips, has treated Lyme patients in Connecticut for thirty years. He – and a growing contingent of doctors – say the CDC has overly stringent and outdated criteria.

STEVEN PHILLIPS: They kind of admitted publicly that their surveillance criteria fails to capture 90% of Lyme cases.

WIZNER: Doctors like Phillips offer alternative tests and treatments but they’re not covered by insurance.

PHILLIPS: The system is kind of broken when it comes to these things and patients are slipping through the cracks. I’m not saying it’s hopeless at all. There’s hope for most patients.

WIZNER: Finding treatment hasn’t been easy for Cindy. The antibiotics likely won’t kill off the bacteria if it’s been in her body for many years.

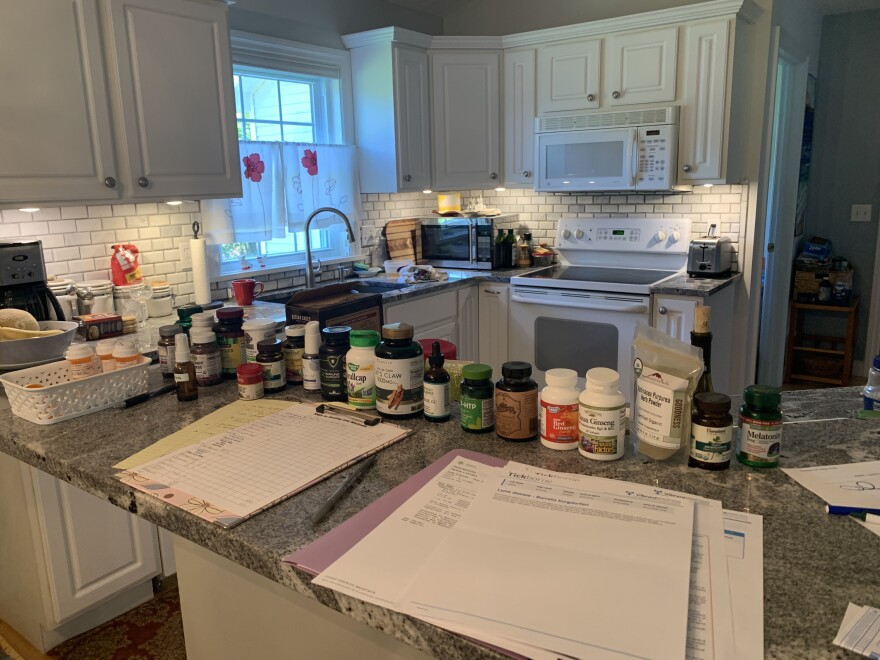

Her naturopath suggested she go the herbal route. She now takes 24 pills each day. And because none of this is not covered by insurance. It cost her a couple thousand dollars.

MINER: I would rather have a doctor say here’s what you do. Here’s what you take. If you have any problems, call me.

WIZNER: She hasn’t started feeling better yet. Some of her medicine actually makes her so ill, her naturopath tells her to stop taking it.

MINER: I have to take breaks from taking the medication, the herbal medication so that I can kind of survive the treatment.

WIZNER: She wonders, what if it’s not Lyme, and the doctors who were skeptical are right?

MINER: Sometimes you know my own doubts start to enter into that. Because I’m not as well as I feel like I should be.

WIZNER: Her naturopath says it could take up to a year before her symptoms go away.

Cindy says her experience with Lyme has been isolating, especially when people disregard her symptoms. She says she’s found support among some people locally, who also have the illness.

MINER: And so if I thought that if I would find other people who had Lyme and been diagnosed with Lyme and find out what they had done and what worked and what hadn’t worked. So it’s like this giant research project trying to heal myself, I guess.

WIZNER: By the end of our hour-long interview, Cindy was barely able to talk.

MINER: I’m already getting really tired. I’m just having a really hard time talking at this point.

WIZNER: There isn’t a cure-all for Lyme disease. Though lots of patients do see a reduction in symptoms over time with various treatments.

MINER: There is hope on the horizon too. Pfizer and a French biotech company are starting a trial for a Lyme vaccine. Though that’s likely years away from getting to market.

WANSCHURA: That was reporter Taylor Wizner.

The bacteria that causes Lyme disease isn’t the only nasty thing ticks carry. We put a call out to you listeners to learn about how ticks-borne diseases affect you.

Roger McHaney in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula says his life changed dramatically after he and his daughter were bitten by lone star ticks in Kansas. They both developed an allergy to red meat and dairy products, the main symptom of this tick bite.

ROGER MCHANEY: It just feels like you swallowed a piece of bread without enough water to wash it down. And usually after that it will be followed with swelling and hives. And the hives may cover my entire body. Then it progresses into where my face swells up. You have trouble breathing.

WANSCHURA: And Logan Clark, a wildlife manager at the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, gets a lot of ticks that latch onto his skin. One seemingly random day, he got stung by a wasp and developed a sudden allergy.

LOGAN CLARK: I had this crazy stomach reaction. I spent the night in the ER. And I saw an allergist the next day. And asked them, how did this happen? I’ve been stung by wasps all the time, this has never happened. And he asked about ticks and mentioned that is quite a possibility.

WANSCHURA: He says now he takes some mitigation measures like tucking his socks in, carrying a tick remover and spraying his clothes with permethrin.

Right now anaplasmosis is a tick-borne disease that’s increasing the most in Michigan. It’s on the rise across the Upper Midwest.

While it’s not as common as Lyme, symptoms can be bad enough to require hospitalization and sometimes death.

Wear those long pants folks.

Today’s episode was edited by Morgan Springer.

Music for today’s episode is by Mike Cavenaugh, Landsman Duets and Caslo.

You can find more stories from the Upper Great Lakes wherever you get your podcasts or at pointsnorthradio.org.

While you’re there, let us know what you think. Rating and reviewing the show helps more people find us. I’m Dan Wanschura. Thanks so much for listening.