Back in the summer of 2014, a botanist named Rachel Goad was on a canoe trip to see a very rare flower. One of the rarest on the continent, actually. It’s called the Kankakee mallow, and it’s native to just one small island in the middle of the Kankakee River, about an hour south of Chicago.

The canoe trip was part of an annual conference for native plant enthusiasts. They’d chosen to meet near the Kankakee River specifically to see this famous flower in its only native habitat.

It’s a lovely little pink flower that grows on six-foot-tall stalks. Hundreds of years ago, it grew in the tallgrass prairies that spanned much of the American Midwest.

But when Goad and the other botanists got to the island, they could barely get off the boat. It was overtaken by thick, large bushes of invasive honeysuckle, leaving no room for most native plants to grow.

The Kankakee mallow was missing from Langham Island. Was this very special plant gone for good?

Credits:

Producer: Claire Keenan-Kurgan

Editor: Morgan Springer

Additional Editing: Dan Wanschura, Ellie Katz, Ruth Abramovitz

Host: Dan Wanschura

Music: Blue Dot Sessions

Special Thanks: The Friends of Langham Island and Stephen Packard

Transcript:

DAN WANSCHURA, HOST: This is Points North, a podcast about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. I’m Dan Wanschura.

It’s summertime, and a group of people are in a canoe, heading out to an island in the middle of a river. They’re going to this island because it’s got something no other place in the world has in the wild: this incredibly rare flower called the Kankakee mallow. It’s a pale pink flower with a yellow middle. It grows on six-foot tall stalks and looks a little bit like hollyhocks.

And according to the Smithsonian Garden in D.C., it may be the rarest plant in North America. Its native habitat is just this 20-acre island in the middle of a river about an hour south of Chicago.

These people in the canoe are part of the Illinois Native Plant Society. It’s 2014. And they’ve gotten together for their annual retreat. And, obviously, because this island is literally the only place in the world where you can see this flower growing naturally, the canoe trip out to see it was the big event.

Rachel Goad was one of the botanists on that trip.

GOAD: I think that we started off down-river a good ways, and we stopped at some other sites and poked around, and then we went to the island at the very last thing.

WANSCHURA: It’s called Langham Island. It’s a long, skinny stretch of land that rises out of the middle of the Kankakee River, which winds through rural farmland in Illinois and Indiana.

GOAD: And what I remember is that we sort of pulled around the corner to park at the island, and it was just, I remember feeling really like my heart kind of sank.

WANSCHURA: What Rachel saw was the island was covered in a thick wall of invasive honeysuckle. It was so dense, they could barely get off the boat. There was no chance any of the Kankakee mallow could sprout and grow under the honeysuckle brush. And that’s when Rachel realized, this very, very rare flower seemed to have vanished from its native habitat. The question was, was it gone for good?

Claire Keenan-Kurgan picks up the story.

CLAIRE KEENAN-KURGAN, BYLINE: Hundreds of years ago, before the Kankakee River was surrounded by farmland, it was part of Illinois’ tall grass prairie land.

Prairie flowers stretched on as far as the eye could see. And Langham Island, in the middle of the Kankakee River, was a particularly beautiful sanctuary for prairie plant species. In the 1800s, one botanist catalogued 400 species on Langham Island alone, including the Kankakee mallow.

After that summer canoe trip in 2014 — when Rachel saw all the invasive honeysuckle, and her heart sank — word spread among the conservationists in the area about the missing Mallow. Trevor Edmonson heard about it and wanted to help.

TREVOR EDMONSON: Hearing the phrase that the Kankakee mallow only grows on this island anywhere in the world, like that is the extent of its remaining natural habitat, is such a draw for anybody, especially someone early on in their career.

He was fresh out of college and had just come to the area to start an environmental conservation job.

EDMONSON: This was a perfect opportunity, you know, to dive right in.

KEENAN-KURGAN: Trevor started asking around to see if there was anything he could do. He got in touch with some of the botanists and conservationists in the Chicago area who’d been on that canoe trip and asked for advice.

About a month later, he put together their first work day. A group went back out to the island. They had to game plan how to restore the mallow’s habitat. They figured, if they cleared the honeysuckle, maybe the mallow could come back.

First they had to figure out where to start on the island.

Trevor’s mentor at his job had an idea. He monitored the Kankakee mallow for the Illinois Department of Natural Resources back in the 1980s and 1990s. He knew they had sketches of the island that showed where the mallow had been growing.

EDMONSON: These maps were like little treasure maps for us to say, this is where we need to start clearing and moving this forward, because we think this is where the mallow seed should be.

KEENAN-KURGAN: No one had seen it since 2002, twelve years earlier. But Trevor and his team were betting on one thing: that mallow seeds had survived all these years underground, waiting for the right conditions to grow. Clearing the honeysuckle was their best shot.

EDMONSON: And so, X marks the spot, and that's where we started cutting aggressively those first few work days, clearing out a little oasis on this one section of the island, this little high quality island of cleared area on the island itself, trying to unlock those seeds.

KEENAN-KURGAN: If the seeds were there, they needed one other key thing: heat.

TREVOR: If we could just burn the soil enough, or the top layer enough that it would get the heat it needed, whatever was in there might germinate.

KEENAN-KURGAN: In the past, that might have come from a fast moving fire sweeping through the prairie. But now, they needed to do it themselves. So, Trevor and the other volunteers cooked up a technique they called a rolling bonfire. They’d make small brush piles and push them along with long poles. And as they burned down, they’d add more kindling.

EDMONSON: We'd have these really long snake-like burn scars through the island back there with the hope that we would hit one of those pockets of Kankakee mallow seed.

KEENAN-KURGAN: Then, they waited to see if any mallow would come. What happened next was closely documented in blog posts from one of the botanists in the group.

Just over a month after the first volunteer workday, the group noticed unfamiliar little leaves popping up by the dozens. They were right along the trails of earth scarred by the fires. Some of the group thought they might just be weeds.But the thought itched at them… could it be mallow?

EDMONSON: None of us had really seen a seedling of a Kankakee mallow before. And so we had to wait till it got to a certain stage.

KEENAN-KURGAN: As the months went by, those tiny clusters of sprouts slowly turned into groups of tall stalks. One person felt the leaves and thought they didn’t feel quite like Kankakee mallow. Another, who had planted the mallow from seed in her garden, said they looked like the mallow to her.

As the stalks got taller and taller, the leaves became more recognizable, and it became clearer that this could really be the famous plant. They built enclosures to protect the plants from deer.

Two years after the canoe trip where they realized the mallow had gone missing, the volunteers saw their first Kankakee mallow blooms. The first stalk that flowered came up in full splendor — five-petaled blossoms with a yellow pom pom head in the middle.

A whole stretch of flowers bloomed at once, almost like they were shouting to the group of volunteers: Look! We are back! Blooming in its ONLY native habitat in the world, on this one island on the Kankakee River.

EDMONSON: It was a group euphoria… there's something full circle about seeing a plant bloom, right, make it to that stage. I don't know, something like, when a plant opens its bloom, it's kind of like it's opening its eyes in a way, right? And so it's reached that peak adulthood, and it's kind of breathing again on the island. It's living in its full glory.

KEENAN-KURGAN: But, their work was just beginning. Just picking up momentum. The island is 20 acres, the size of about 15 football fields.

EDMONSON: We had just cleared just a fraction of what we really needed to. We had to keep going.

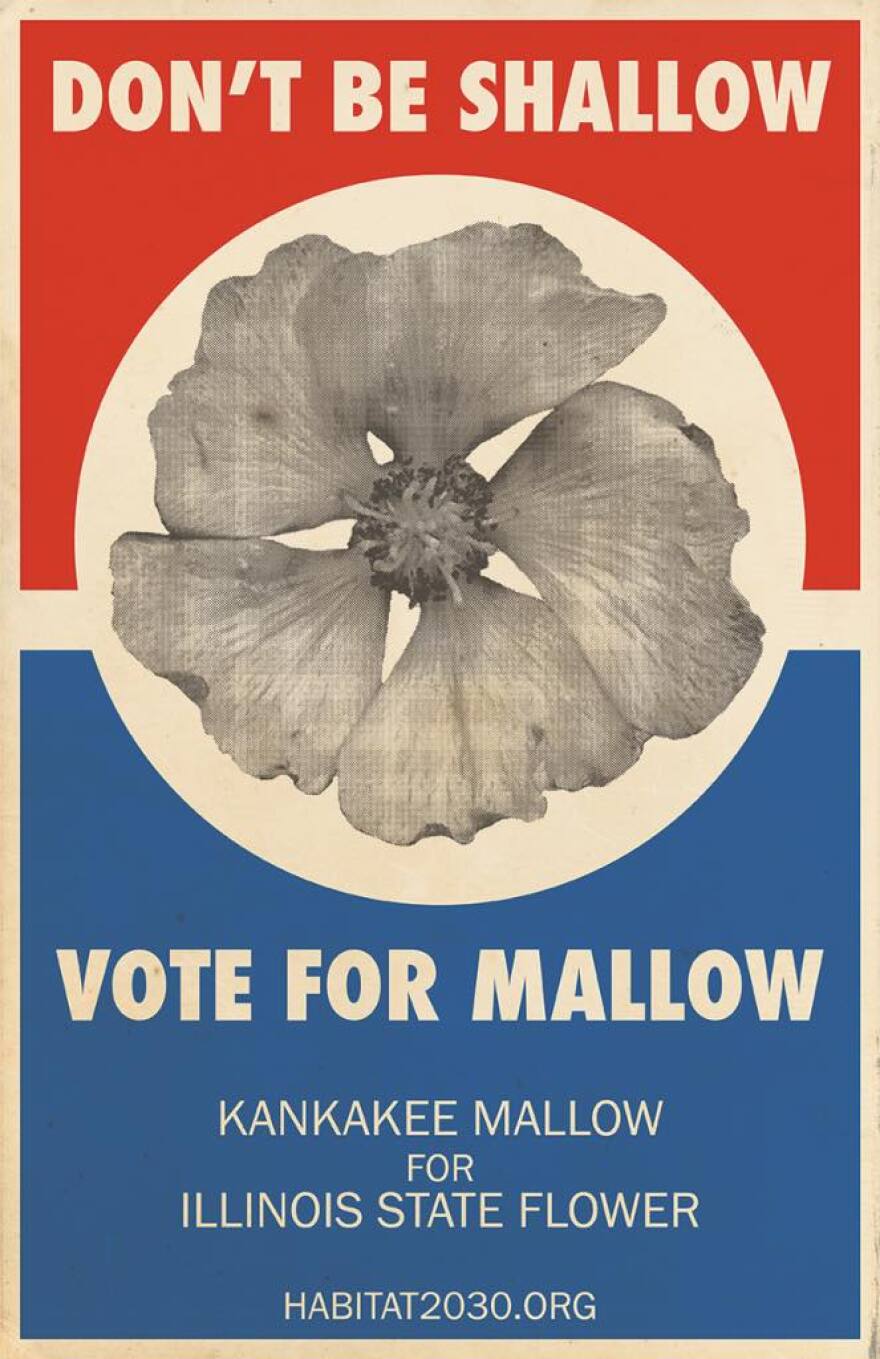

KEENAN-KURGAN: So, that’s what they did. They cleared more and more honeysuckle. And as they did, clusters of new plants popped up from the soil underneath. Within those first few years of the project, there were hundreds of mallow plants blooming on the island. They had teams of volunteers from all over the Chicago region coming to help. One volunteer even started a campaign to make the mallow the state flower of Illinois. It never took off, but they had campaign buttons: Don’t be Shallow, vote for Mallow.

In 2020, Trevor got a new job and his life got busier. He had to hand over the reins to the other volunteers. By then, they had cleared about a quarter of the island and were continuing to clear the rest. And if they stopped, the honeysuckle could just take over again and smother the mallow. There was a lot of work to be done.

These days, there’s a smaller but dedicated group of volunteers who show up each week to cut back honeysuckle and protect the mallow. I went out with them one Saturday this summer.

The group sets off for the island from the shore in a little rowboat loaded up with gardening tools. We get to the island in just a minute or two. It’s long and oval-shaped with a kind of bluff on the top, and a steep slope on the back side.

The volunteers have made a lot of progress since Trevor left. About two thirds of the island is cleared now. Steve Bohan is the leader of the group now. He’s in his 70s. White hair. Casually dressed with a baseball cap.

KEENAN-KURGAN: Does your hat say invasive species on it?

STEVE BOHAN: My hat does say invasive species. And a lot of people ask me about it. We were on one field trip with the Native Plant Society and a guy said, “Well, I like your hat, but I have to ask you, from the get go, Are you for or against?”

KEENAN-KURGAN: And what did you say?

BOHAN: I said, “I'm against.” I'm against, although, frankly, you don't get more invasive than humans. So, whatever.

KEENAN-KURGAN: That is a good summary of Steve’s attitude. He’s a pretty matter of fact guy. But, he loves Langham Island. He lives about as close to it as possible, on the banks of the river.

BOHAN: It's such a special place that once we started clearing all the honeysuckle, we saw quite literally hundreds and hundreds of native plants spring up on their own.

KEENAN-KURGAN: At this point, the possibility of discovering new plants popping up is the most exciting thing for Steve. He’s actually kind of over seeing the mallow. He sees it every week.

BOHAN: You know, well it’s cool, but I've seen better. I mean, the individual flower itself is very pretty, but it's not impressive.

KEENAN-KURGAN: So, he’s setting the bar pretty low for one of the rarest plants in North America. Steve takes me over to a large enclosure where the mallows are protected from deer. This is one of the spots that was marked on the old DNR maps. Looking at the mallows inside the enclosure feels like looking at a museum display. Like you’re in the natural history museum and this is the Kankakee mallow exhibit.

KEENAN-KURGAN: I mean, okay, maybe it's not the fanciest flower I've ever seen, but they are really nice. They really are. I think they're pretty special.

BOHAN: Yeah, they are.

KEENAN-KURGAN: The delicate blossoms are almost too perfect. They look kind of like if you asked a kindergartner to draw a pink flower. And they grow on these impressively tall stalks — hundreds of blossoms right at eye level. They are all in bloom right now, completely filling their large enclosure.

BOHAN: I don't know how big this is, 40 feet maybe diameter, and I've never seen it so full of mallows. So that’s really good … It's just gorgeous. It's absolutely gorgeous.

KEENAN-KURGAN: The only thing that stops Steve from coming every week is if the river is frozen or flowing too fast to safely cross.

BOHAN: I'm 70 years old. My shoulders jacked up. It would be the easiest thing on earth for me to just say, "Screw it. I ain't going today."

KEENAN-KURGAN: But it’s satisfying.

BOHAN: At the end of every workday … I just look at the island, and it's like, wow, we've cleared all that. It's just awesome.

(weeding noises)

MOLLY ULRICH: You kind of just weed your way across the section that you’ve decided you're gonna clear.

KEENAN-KURGAN: Molly Ulrich, a volunteer, is cutting back the honeysuckle bushes and other invasives and dabbing herbicide on the stumps left over. Molly grew up in Kankakee, but she didn’t know about the mallow until she was an adult, when some coworkers in Michigan told her about it.

ULRICH: They were like, “Oh, you’re from Kankakee, like the mallow?” and I was like, “Like the what?”

KEENAN-KURGAN: Today she’s hunting for regrowths of invasive species in a spot the team has already cleared.

ULRICH: You almost, like, develop the eye for it after you have some practice.

KEENAN-KURGAN: She chucks each cluster of chopped down honeysuckle into a big pile and then continues moving down a little goat trail the volunteers have cleared for their work.

You might be wondering why they even bother to do all this work for one little flower. I mean, does it really matter if it lives or dies? For Molly, like Steve, it’s not really about the mallow. She says the mallow is like the mascot for the greater goal — restoring the ecosystem that used to thrive here.

ULRICH: Illinois is the Prairie State, but we've lost over 99% of our prairie. That’s the bigger picture I like to keep in mind: like how many of the species that relied on that 99% that’s just gone.

KEENAN-KURGAN: This work on Langham Island feels like something she can do to push back against that loss.

ULRICH: 'Cause sometimes it can feel a little bit like you're just stuck contemplating the doom of it all. But seeing it come back with just a little bit of attention is also one of the things that gives me the most hope.

KEENAN-KURGAN: It’ll continue to take time and effort, but the island does feel like a place where people are practicing a different kind of relationship to nature. One that takes some attention, and care, to be kind of wild again. Here’s Steve.

BOHAN: There's a lot of people that say they appreciate nature. You know, how deep is that appreciation? What are you doing to help restore the balance?

KEENAN-KURGAN: That’s what he’s out here doing today, restoring a balance. A balance that lets one, slightly translucent, delicate pink flower bloom.