A group of researchers used data on Michigan fish populations that date back more than 80 years.

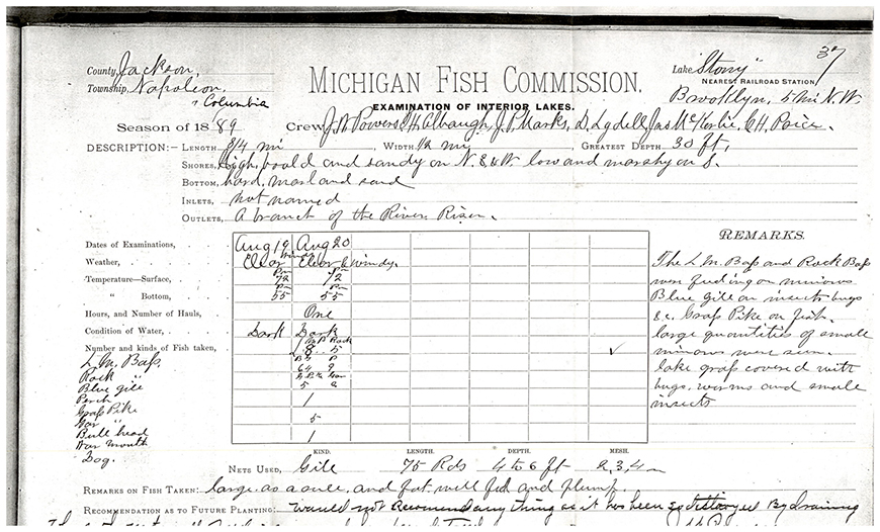

The records, initially kept on handwritten index cards, were digitized a few years ago, allowing scientists to analyze them alongside more recent fish data plus indicators of climate change, like surface water temperature.

“There's this general trend that with climate change and warming temperatures, many animals are getting smaller in their body size,” said Peter Flood, lead author of the study and postdoc at the University of Michigan. Though there are occasionally exceptions to that trend, he said.

The study looked at fish length data for various species at different ages. Researchers found that many species, particularly when they’re young and old, are getting smaller. That can have implications for ecosystems.

“The youngest fishes getting smaller makes them more vulnerable to predation, which could have implications for sustaining healthy fisheries,” Flood said. And as for older fish, being smaller may mean they have fewer eggs.

Flood said there are several hypotheses for why fish are getting smaller, and they vary by species.

For cold water species that are shrinking, like northern pike, “[the fish] are no longer finding the thermal habitat within a given lake that [they] would prefer, and the conditions for optimal growth just aren't being met,” Flood said.

Surprisingly, even warm water species like bluegill can shrink if water temperatures heat up. Flood said it’s possible that since older fish are thriving and having more offspring, there might be more fish competing for the same amount of resources, making each individual fish smaller.

Some research, though, bucks that trend: a previous study shows certain species, including lake whitefish, might actually be getting bigger with climate change.

“A big part of the scientific method is doing similar research or even trying to replicate studies again,” Flood said. “Because there are exceptions to this general trend of shrinking, we're now able to weigh in with a unique data set because of the crowdsourcing aspect [of this data] … We’re able to provide support for that overall trend of shrinking, with some nuance.”

The research was only possible because of monitoring programs on Michigan's inland lakes that began in the early 20th century. Researchers for this study relied on many of those paper records, digitized recently, to assess data spanning from 1945 to 2020.

Flood said having those decades-old snapshots of ecosystems were crucial for this study.

“Part of what made this study possible was folks going out and collecting these data in the early 1900s — long before humans were aware of or really concerned by climate change,” Flood said. “I think it really lends itself to the importance of … monitoring our natural resources and ecosystems to understand what they look like now.”

Data collected today "could be used in 50 or 100 years for some purpose that we have yet to imagine,” he said.