This reporting is made possible by the Northern Michigan Journalism Collaborative, led by Bridge Michigan and Interlochen Public Radio, and funded by Press Forward Northern Michigan.

STAR TOWNSHIP — In 2021 and 2022, auditors warned the board in Antrim County’s Star Township that they had serious concerns about the township’s financial relationship with “a group of individuals who call themselves the Star Township Fire Board.”

The township turned over its fire fund money — nearly $260,000 in 2022 — to the board to run the Fire Department, whose chief is married to the township clerk.

Problem is, the board “is not a legal entity separate from Star Township,” auditors wrote, and “the township does not maintain physical custody of the fire department’s cash, nor does it approve expenses prior to payment.”

Auditors also criticized the township board for failing to maintain “generally accepted accounting principles.” The township failed to submit audits to the Michigan Treasury in 2023, 2024, and 2025, putting the township’s state revenue sharing income at risk.

Star Township has about 1,000 residents, one of hundreds of small townships in Michigan where such problems pop up frequently. While many states have towns and counties, Michigan’s network of townships means the Great Lakes State has more municipalities than even larger states like California and Texas, and most of Michigan’s rural township offices are only staffed part-time.

Often short-staffed and run on a day-to-day basis by elected officials who don’t always take the training offered to them, auditors repeatedly ding rural townships for failing to properly manage their finances, and townships frequently struggle to correct those problems.

The Northern Michigan Journalism Collaborative surveyed audits of the 51 townships in Antrim, Grand Traverse, Kalkaska and Leelanau counties and found 42 (82%) have received at least one disciplinary letter from their auditor and/or the Michigan Treasury in the last seven years, including seven townships that received deficiency reports in each of the last seven years. In nearly two-thirds of the townships surveyed, Treasury required the township to identify corrective actions.

“You can’t help but catch some forms of fraud and abuse or, at a minimum, maybe not fraud and abuse, but extreme inefficiency.”ROB CARSON | Networks Northwest

Auditors find problems in big cities, too. Of the 10 largest municipalities in Michigan, seven have received deficiency letters from auditors since 2018. But in bigger communities with full-time staff, auditors tend to find fewer deficiencies and those problems are corrected more quickly.

Most commonly, auditors said townships had one official performing multiple accounting tasks without independent review or approval. While audits didn’t find specific examples of misspending, they noted that the lack of oversight creates the risk for fraud.

“You can’t help but catch some forms of fraud and abuse or, at a minimum, maybe not fraud and abuse, but extreme inefficiency,” said Rob Carson, regional director for community development at Networks Northwest, which assists small local governments with some administrative tasks.

In Star Township, Clerk Phyllis Hoogerhyde was not available for comment. Her husband, Fire Chief Pete Hoogerhyde, wouldn’t comment on the township’s relationship with the Fire Board.

Pete Hoogerhyde, who is not an elected official on the township board, said he was “just visiting” with auditors Monday — not acting on the township’s behalf — and said the delinquent audits would be submitted to the state by the end of the week.

“We just need to pay the auditor,” he said while picking up a check for the auditor from the township offices.

No experience required

Michigan has 1,240 townships covering 96% of the state’s landmass and governing more than half of its people. Tim Kuehnlein, professor of political science and history at Alpena Community College, called townships “the building blocks of our civic structure,” responsible for everything from elections to cemeteries to parks to first responders.

“I mean, no offense, but the president isn’t doing all that,” Kuehnlein said.

In townships, elected officials not only serve on the governing board but also staff the township offices. State law sets few restrictions on who can serve in those positions.

“If you’re 18 years old, you can be a treasurer for a township,” said Carson, of Networks Northwest. “You don’t have to have an accounting background, you don’t have to have any sort of background that would display that you have an understanding of financials.”

Eric Lupher, president of the Citizens Research Council of Michigan, called it a “lack of sophistication.”

“You’re getting average, everyday citizens in the world of political science. Call it ‘Jacksonian democracy,’” he said.

Andrew Jackson was, according to Lupher, “of the opinion that government should never be so complex that an average, everyday person couldn’t do the work.”

The Michigan Townships Association offers training to township leaders, and association spokesperson Jenn Fiedler said “more than 99% of Michigan’s 1,240 townships are members. Last year, officials from more than three-quarters of our member townships participated in some form of MTA training.”

Lupher compared those training sessions to going to church: “The ones that need redemption aren’t showing up.”

Especially in rural townships, township offices are staffed part-time — “so you’re not able to get a hold of someone,” Carson said — and a number of township officials head south for the winter, leading to canceled monthly meetings and closed offices.

Five of the 15 townships in Antrim County have either canceled winter meetings in the past three years or have failed to post meeting information on the township website.

‘Over my head’

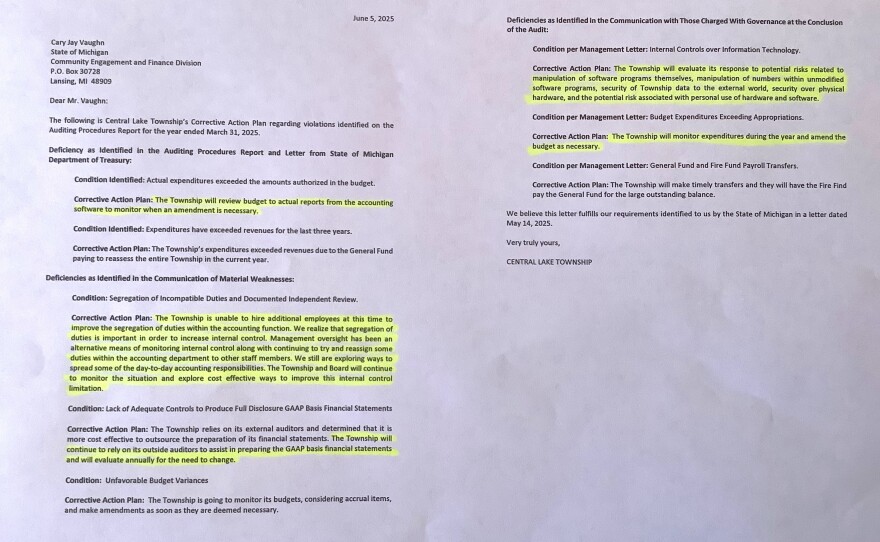

Near Star Township, Central Lake Township’s auditors have identified a laundry list of financial shortcomings.

Over the last five years, township leaders there have failed to maintain documentation for credit card transactions (2020, 2021), failed to correctly reconcile bank accounts (2021), failed to log checks and budget amendments into the township’s accounting software (2020, 2021, 2024), paid out undocumented mileage reimbursements (2019, 2020 ), overpaid employees (2023), failed to properly secure township data (2020 through 2025) and spent more than they took in three years in a row (2019, 2025), auditors said.

Central Lake Township Clerk Judy Kosloski, who is married to the township treasurer, called the auditor’s findings “form letters” that don’t pertain to “anything crucial financially.” She couldn’t explain the specifics of the township’s financial checks and balances but said “it’s a step-by-step depending on whatever I’m doing.”

When, in a hand-delivered letter, the Central Lake Downtown Development Authority accused the clerk and treasurer of nepotism, Treasurer Larry Germain replied, “We’re elected officials. Nepotism accusations don’t apply to us.”

Central Lake Township has had to file corrective action plans with the state in four of the last seven years. The last two years, the township appeared to copy and paste large portions of their answers from previous letters to the state.

Kosloski, the township clerk, maintains that she has never seen those documents and said she refers such matters to the auditor because “it’s over my head.”

In some townships, audit findings are quickly addressed.

In Grand Traverse County’s Green Lake Township, auditors in 2021 and 2022 found, among other problems, undocumented credit card transactions, incorrect mileage reimbursement, and overdrawn tax collection accounts.

Township Supervisor Marvin Radtke said the issues were corrected by recognizing “we had a number of policies that were out of date.” The township “worked with auditors and lawyers to get policies up to date and in compliance.”

Employee turnover has also been a problem, but Radtke said township leaders are working to “have procedures in place so anyone that steps in can do the job.”

Auditors in 2023 thanked the township “for their careful attention and corrective action taken related to issues identified in the prior audit.”

Citizen recourse

Often, rural township voters get no choice in who ends up running their township.

In the 2024 election, 94% of treasurer and clerk positions in Michigan were uncontested, according to election tracking site Ballotpedia.

The Central Lake Township treasurer’s position was contested unsuccessfully by a Democratic nominee. Only one Democrat won a township election in Antrim County in 2024.

Matt Gabris, a Central Lake Township resident and business owner, said he’s “going to go down every road I can and see where it leads me” to force the township to take control of its finances.

He’s submitted multiple Freedom of Information Act requests. He’s hand-delivered letters to the board. He may sue if his FOIA requests are unsuccessful. He also plans to send letters to the Michigan Treasury, all to put pressure on the Central Lake Township board to make changes in the way they handle township finances.

“We’ve got a diseased section of the forest that needs to go,” Gabris said. “It’s really a sustainability fight.”

His last resort would be a recall election, which Central Lake Township officials will be eligible for starting in January. There were 37 recall votes in Michigan in 2024, including the removal of one official from Yates Township near Baldwin.

Gabris knows people who are interested in the clerk’s position if it were to become available.

“It’s a very well-paid position,” he said. “Over $51,000 a year. There are people that are well-qualified in the township that are making a lot less than that.”

If he doesn’t see improvement in the three years before the next election, Gabris is considering running for township supervisor.

“So far,” he said, “change hasn’t come.”